Anonymous, 51

Grbavica (Sarajevo), Bosnia-Herzegovina

“We were laughing in their face. We say, “We’re not going to the basement for two or three grenades.” [Laughs]. You don’t go to the basement for two or three grenades. That’s when you would go to work. Everything would be functioning normally. We go to the basement when there are hundreds of grenades falling, because then you feel like, “Oh I could actually die,” and-and-a that decision to go to the basement is risky. And then that you could die.”

Interview initially conducted in BCS.

Tell me about yourself. Where you grew up, where--

--Okay

What was life like? How did you spend a typical day? Pre-war, I mean. Before everything.

My… my name is [Anonymous]. I lived in Grbavica in Sarajevo for 22 years. From when I was born, all the way until the war I lived there. And I grew up there in Grbavica, I have uh my father, who is still alive, my mother unfortunately passed away, [takes a breath] and I have a sister, And I grew up, like I said, in Grbavica. I went to elementary school there, and in Treća Gimnazija for high school. Then I first enrolled in medical school. I finished one year of medical school and then I transferred to dental school. I was in my third year there when the war started.

And… before the war life was really good [smiles]. It was so nice. Like how life is for young people here in America, how most young people enjoy themselves. They live life, and onaj… they have friends from all backgrounds. I lived that way in Sarajevo. Sarajevo was always full of people and I always enjoyed it, not just being surrounded by Sarajevans, but meeting people who weren’t from Sarajevo. I had a lot of friends who weren’t Sarajevans. Especially ok- during those student days, I had a friend from Zenica, from Trebinje, a friend from Africa, a friend from Iran… really close, good friends. And of course Sarajevans as my friends. That’s how Sarajevo was. The city was that way, people lived like that. We were- we could be divided into those who were in the community and those who weren’t.

“The community” were those people who accept and like everyone, as long as you are a good person. People could be split into good men and papak [laughs]. Good men are those who can keep their word, who have quality in their, how should I say, personality. The selfish ones are those… who are simply selfish. I don’t know how I would explain the word papak. It’s a very hard word to explain… Sarajevans understand it. Uh… it doesn’t mean that they are stupid, it doesn’t mean that… simply, they aren’t part of the community [laughs]. They aren’t for everyone. Sarajevans live for everyone. Literally, like, for the community. Those are Sarajevans for you. That’s why Sarajevo is loved. And whoever comes to Sarajevo can be a Sarajevan. You just have to decide to be papanizma, you have to decide to be open-minded and accepting of people to be in Sarajevo.

That’s why I will always love Sarajevo. Regardless of who lives there and what changes, Sarajevo has… my life was wonderful in Sarajevo, until the war.

Yep… and then after the war I came here, to Houston, in ‘95. And since then I’ve been living in Houston. That’s why I always say, I lived there for 25 years, I lived here for 25 years, Now I’m half and half– I’m Bosnian-American now. And I feel like Bosnian-American because I’ve changed a lot. I wouldn’t be able to live there anymore, with the style of thinking that most people think. And what is funniest, when I came here, I realized that I was never part of the… “group think” over there…People who are so close-minded, who just see the interests of their own group. Simply, I was always civic-oriented, for everyone–

I looked at everyone the same, and I will always stay that way and I’m proud of myself for that. And my husband is like that and we are raising our children like that…

That’s the only way to be happy–non-judgemental and open [pause] to people and experiences, but still cautious, we need to be careful because all kinds of people are out there who don’t have good intentions. Do you agree? [smiles]

When did the war start for you? Was there a specific moment when you realized “Oh, this is happening?”

[Through a smile] Well I woke up in the morning, when it was…what date was that? I always forget. Was it the second… of April? Was it that? [pause] The interesting thing this was that before the war started, I think it was Eid, it was the beginning of April, but… wait, I’m mixing it up a bit… anyway, they threw a grenade in Grbavica… I’m mixing up those dates. Let me see here. Can you pause it [smiles] the interview? If you are recording. So I can look for it [in my journal], to see when I wrote when the massacre happened, then I’ll know approximately. [pause] I have the date here somewhere…

Okay. The second of May. The second of May in ‘92 was the massacre. You couldn’t go to Grbavica anymore. However, before that, in April. In April was Eid and they decided that… I don’t even know uhm… we woke up, I think that was the second day of Eid, around the beginning of April, something happened at Baščaršija. There was some problem, someone here was… fighting, maybe my husband knows, maybe he remembers. But I mostly know this: how I felt so stupid when I got ready in the morning to go to college. I got dressed up, got my things ready, and then I was going to the trolleybus station.

I’m standing at the stop, other people are standing, we’re waiting, waiting…there’s no trolleybus. There’s no bus, no taxi, no nothing. I was standing like that for about a half hour-hour and I think, “What now? I’ll go back home.” It absolutely wasn’t clear to me what was happening. Nobody anywhere. Just those of us who went out to the stop, who didn’t know. And… I went back home and then on the radio, on the television, they said that war had started in Sarajevo.

“What?” and I remember that, I remember that exactly–when I was waiting and when I came back home. And then things just started.

They started to come down from above, what I was telling you, in those jeeps, black jeeps, three or four of them, open the windows of that jeep, they take out their machine guns, machine guns and then they would shoot in the air.

And then, ‘We’ll kill you all, Alija balija!’ That's what it was. Saying that Muslims are ‘Balija,’ and then since Alija was the president, they shouted that, “Alija Balija.” Uh and they said… they said all kinds of things.

We were on the ground… because our building faced that intersection that went uphill to Vrace directly. Vrace was that– from Vrace you went downtown. And that intersection was in front of our building. So that they would come down from above, that was when they frightened people, there wasn’t a blockade yet, but they came down and frightened people, shouted all kinds of things, they said all kinds of bad things, and then just turned around and went back. And then we were all truly scared.

My mother was anxious most of all. As depressed as I was, with school like that, she would get so scared. She had a weak heart, uh… Since birth she had a heart condition, so she could never do anything very active, but I know that her doctor always told her that she can’t get too stressed, or get too strained… those jeeps would stress her out so much, she would feel so awful and it was difficult to watch. And then we decided to go stay with a family friend, for her health, so that she doesn’t have to live through that every day, stay alone. Imagine that you are alone and someone comes to your door, y-yelling: “We’ll kill you all!” It’s awful. And onaj… if at least someone was with her then maybe it would be easier for her, she wouldn’t be so scared. So we stayed with friends.

That’s what you might have heard…that we were with family friends in the JNA. We went over to them until things calmed down a bit, because even though we didn't know yet that there was a war– everyone talked about a war but no one can believe it–we came to them, and then we went to Grbavica every few days. And why? Because in that apartment, with those family friends, there were a lot of us. Uh the two of them, their daughter, son-in-law, and two sons… that means there were six. And with us four, that was ten. Ten of us were in a three-room apartment. And one bathroom. Imagine ten people with one bathroom. And then we would go to Grbavica, to shower, to get ready, and… we would take turns, my sister and I. Sometimes she would go with our father, and sometimes I would go.

And one day, this is interesting… One day, in the evening, I told my mom: “Hey, I’ll will go tomorrow with dad… to wash up” and we would change our clothes, do laundry, do things like that so that we weren’t putting our family friends out. And I tell my mom like that, “we’re going tomorrow, dad and I, we’re going to wash up. Do you need any clothes to change into?” She says “You won’t go anywhere.” [smiles] I’m looking at her, dad is looking at her, “Why won’t we go, we go every few days, someone needs to go.” Either dad and I or Sabina and dad. Two of us always went to do what we needed.

“So why can’t we go?”

“You won’t go anywhere tomorrow, I c-c-can’t l-l-let you go.”

“So why can’t you let us go? What’s the problem?”

“You won’t and you won’t-” she would just say that, “You won’t go anywhere tomorrow, don’t bother me any more about it, don’t make me sit down sick. Nemojte prejedat na muku.” “No one will go anywhere tomorrow.”

And dad tells me: “Well,” he says “leave her be, maybe she got stressed out from something she heard, or saw, onaj… we don’t have to go tomorrow, we can go the day after.” Like, “let her calm down and then we will go.” Well ok.

I was sorry that we couldn’t go, because I couldn’t shower. [laughs].

The next day, we woke up, when the main news on the radio, “You can’t go to Grbavica anymore, to Grbavica.” [pause]. On that day, when we were supposed to go. They they put a blockade on the bridges and they didn’t let anyone to go in or out.

“Mom, were you… how did you know? What’s going on?”

We were so confused like… “Did you hear from someone that Grbavica would be blocked off?” [laughs] “What’s happening?” She says, “I had a bad feeling about letting you go… that I had a feeling that you shouldn’t go.”

Something was giving her that feeling and that’s why she didn’t let us go.

She had a feeling, but that was not the only time, she had a feeling three times later on. So, that’s when we learned she had some ability… But that was amazing.”

She saved you--

--She saved us from going there and being there [during the blockade].

“But she never said like “I have a bad feeling, something is gonna happen”, you know… something like that. She just told us “No, you guys can’t go. Please don’t ask me, don’t push me.” We just couldn’t go. That was pretty much uh the way she talked to us. And I was very upset. I was really mad that she wouldn’t tell me why because I always liked for things to be explained to me, for whatever. “I can accept anything, but don’t just tell me: ‘No, just do it, just because I said so.” Like, explain to me so I can make a decision. [laughs] give me a reason.

And she didn’t–

-- Oh no. The second time that something like that happened… hmmm oh… This massacre… [sighs]. That’s what I was… writing about how I was looking for my sister. Uh… you heard that–maybe you heard it.

There was a line for bread. And everyone [smiles]... how should I explain it to you, how close it was to where we lived. Uh like this. “Let me.. Let’s have this as the street where it happened. This - their house is right there. I mean, their building. Uhh I’ll put this around, so this is just - let’s put this as the building… So yeah, this is pretty much how it looked. So this is one building, this is one building, this is one building and this is the building. So in this building my”- family friends lived. These two are on the side. And here in the middle was uh… uh garden. Summer garden. For uhm a restaurant. What was the name of the restaurant? [pause] That’s very important, very important. You can ask your father, for God’s sake. What was the restaurant called… but I know Sula from Dubrovnik, onaj, he was the owner of that restaurant. I can’t remember the name.

Let’s say that this is that restaurant… you understand? This is the b-building. “Main entrance is over here, from this street.” But this here is the “square,” this is “inside the buildings. And main entrance is here. Then here, main entrance is there. And uh, what did I say this side was… I’m trying to recall”--

--The building.

And the restaurant was here. Like this, ovaj. So that means the restaurant was, you enter through here, the restaurant was here. And here was also a building and you exit here on the street.

That morning, the grenades woke me up.

But before I tell you about that, think about my mom– The night before. We were living with them for some time already- let’s just see when was the massacre [smiles, flipping through journal] I have the date, in this letter, it’s good that I wrote it down…[pause] Uh wait, where is it…Aha. The massacre was on the 27th of May ‘92. Hey, and the day before they came in, came into the apartment and took everything from us. That was before that massacre. So the 26th of May, within a month of the start of the war, they came into our apartment. And the 27th of May was the massacre.

We were already living [with our family friends] for, like, for a month. And every morning– there were three men in the apartment: our family friend, his son-in-law, and my dad–every morning the three of them would go out and they would go to different places to find bread. How many of us were there- ten of us. They’d go to buy bread, to have something to eat, whatever the women could cook. And onaj, they did that every morning. And they bought, I don’t know, a few loaves of bread, and we ate it… so that the night before the massacre, my mom went to the room where we kept the bread, whatever was left. And that night she went and looked at the bread, counted it, and realized that they didn’t have to go to buy bread tomorrow. We could just have that.

But she said again that something was telling her that they shouldn’t go buy bread. And she never did that before [counted the bread], except for that night, the night before the massacre. And not once before, not a single time before, did she say not to go the next day but that night.

“Don’t go tomorrow to buy bread. We have enough for tomorrow.”

“Okay.”

That morning… I woke up, so I was in this building. Uh, here was the restaurant, and here was that building, and here was the street where the massacre took place. This was just a small garden. Not a big garden. Let’s say the garden is the size of… mmm like that… here’s me, here’s the garden. It wasn’t big at all. So like what I have here, where the pool is, about “that size.” There were, uh, four chairs to sit on, here. So one, two, three, four, so you can sit. Because that is, you know, like a pathway, you know, between the buildings there isn’t any greenery, nothing, the buildings are tall, so only that space, he used it to make a garden for that restaurant and that was our pathway when going to… when going to college Sabina and I, instead of going on the main pathway and going around, we would just go to that back “Exit” through his restaurant, we would come out here and carry on toward the college. So that shortened the path going straight instead of going all the way around. And he knew us well, he was a family friend of Rizo since his family was in Dubrovnik when the wa-war started, he had a wife and two sons, unfortunately one of his sons was killed. Onaj, he would come to us every night to watch the news with Rizo, sitting and talking and watching like that… Nice man, very nice.

And onaj that morning, screams woke me up. I didn’t hear any bombs fall, I was a very heavy sleeper. The bombs really had to knock against the building for me to hear them, but that happened often, and when they fell really close to the building or if they hit the building I knew they were there, because it would wake me up. Otherwise if it were the street, next street over, I didn’t hear it, I would have slept. I was always heavy sleeper. I didn’t hear any bombs fall but screams woke me up. Awful screams aw-awful screams. I’ll never forget those… that was indescribable, no horror movie can describe it. Really… so many voices, like a hundred voices.”

“Oh, no, oh no mother!”

“Help her!”

Like that. Terrible.

“What happened here, everyone!”

Here [gesturing to arm], I get chills when-when I remember. I was sleeping like that, with a lot of us sleeping on the floor, and I woke up thinking ‘God what is this, why are people yelling like this, why is it like this, these desperate cries from people?’ I came here into the room with my family uh to see what was going on, they were already up, they said: ‘Here they’re saying on the radio that there was a bomb, that it fell here near us.’

And they turned on the television… and there was a recording immediately. That was at 9:30 in the morning. There was a live recording immediately on what happened–they talked about it later ‘that was set up, they were targeting themselves, where did the camera come from to be able to record it immediately?’ that was what they said, in Belgrade. But why was there a camera there? It was for the neighborhood art exhibition and they came to film the art exhibition that started in the morning at 9:00, this happened at 9:30 and when that happened.

They tell us, “Turn on the television! The recording is on the television!” Uhhh awful, awful, the worst part was that my had a uh light yellow jumper, the color of a lemon. Maher wool, fluffy,”nice, and was wearing it this day, I ask them what she was wearing, my mom said she was wearing that yellow sweater.

“When did she leave?”

“Five minutes ago.”

“Oh my God. Five minutes ago.” And we’re all thinking, did she find herself there too? During the bombings? Because she exits the building right where it happened or she passed right by it or is to the left of it, but it’s all still there, right there. Right there that happened. Oh my God.”

I told my mom “Go, to the hallway and I’ll look for her. I’m looking at what… I don’t know if you’ve ever seen pictures from the massacre, don’t if you haven’t, don’t…I can only say this: feet, severed arms, legs hanging... Onaj, a Sule, the owner of that restaurant, he came over that night to watch the news, everything… lost and all bloody. The whole day he was picking up body parts in some bag [pause]... the whole time while they were helping… when they came in to help people, more snipers were shooting at them. And then more snipers somewhere set up again.

They targeted the bread line on purpose and even then snipers were targeting those who the grenade didn’t kill… Awful. Mostly, I know that Sule just said that onaj “I spent the whole day helping carry the wounded and then picked up parts of fingers and others, legs…” Awful. That was such an awful experience.

And now I’m watching that recording and I’m looking to see if Sabina might be there, I’m looking, I’m ono praying to God, to not see that yellow jumper. I don’t see it, but at one point. it films a woman, you know who is standing there, she has a bun in her hair who grabs her head and yells Oh Sabina! My Sabina.’ Oh my God, that k-k-k-knocked me out. I’m thinking, “That isn’t a friend of hers from college, that they haven’t met and that it isn’t my Sabina now. To know which Sabina it is, that woman was mainly helping Sabina… Still to- I didn’t dare tell my mom. Thankfully I took my mother to the hallway to sit, and I was watching like this [face in hands, edge of seat].

I didn’t see that jumper. That was good. The phones were not working, they cut them out. There was no electricity, no water, no phones, no nothing. My dad left to go to work, but he heard what happened on the radio. And his laboratory was close by, with a friend by Skenderija. And then he walked home quickly. But we didn’t hear anything about it at my sister’s university. She went and I don’t know, did her business. But she said she was in Dalmatinska. Dalmatinska street in Sarajevo is where you go from Tito’s street uphill toward the university and like this it gets pretty steep.

And she said she was halfway up that street when she heard the grenades fall. That means that five minutes earlier she had walked by where the grenades were. And she says that she heard them falling non-stop. They were falling ‘non-stop,’

That was a part of our lives. And she said ‘I heard them and I just carried on toward the university.’

My dad came, he said “Ok, I’m going to look for her up there.’ That waiting… they came home somewhere between 12:30 and 1:00, something like that. We were waiting in the hallway. And our family friend had an Austro-Hungarian style apartment, so it had high, like, vaulted ceilings and a large glass front door, they were really pretty. And we were looking through that glass door, waiting in the hallway, and we saw a silhouette, but you only saw something “blurry.”

And then we saw that yellow jumper.

When my mom and I saw that yellow jumper, both she and I… we just hit the wall. And it happened to-to her. She was sitting, and she started shaking so hard. Her jaw was literally chattering. Her jaw was shaking as hard as her hands. You know, some strange feeling, and I had never seen anything like that before… You know when people fall and they shake, but she– don’t know if she was c-conscious. Really, she felt so…

-- Like shock.

Shock. Sabina came in.

“Mom, I’m ok, it’s me, I’m ok.”

Nothing, she [my mom] just continued shaking. And then Sabina slapped her really hard, we laughed about it later, but at that moment it wasn’t funny. Then she came back to herself and stopped shaking. After she somehow recovered from that state, then she came back to herself. And then we asked my mom, “Mom, how did you know to tell them not to go buy bread in the morning?”

“I don’t know.” She said “Something gave me the feeling, again I felt- that they shouldn’t go buy bread in the morning, that I should check to see if we already had bread. When I saw that we had enough, “Don’t go to buy more bread. You don’t have to go.”

That was the first time she had said something like that in all those months, on the eve of that massacre that happened in the line for bread. If one of them went to that line or if all three went, either they would be wounded, or they would be killed because there was no one who wasn’t at least wounded. They dr-dropped the grenades directly on them. And that was called the Ro-Rose of Sarajevo, I think. They painted it, I don’t know if you’ve seen it in Sarajevo? They painted it in red. My good friend’s father, who was a pharmacist, was killed there. He just sat down, he was across the street, where they sold shoes, it hit him somewhere and he just sat down and… It shows him too, but the recording is awful don’t watch it.

The third time… When she saved our lives… It was summer, beautiful weather, really nice. I think that this was the next year, in ‘93, because I was already with Enis and we started dating in April of ‘93. And anyway, Sabina and I came back from university, it was a beautiful summer day, nice weather, and it was the armistice.

It was the worst when there was an armistice. When they signed an armistice, you knew that they would drop a few grenades. And why? Because they know that everyone thinks that there is an armistice and that they can walk around, and wherever they drop it they can kill someone. It will hit someone. That was a must–for them to hit someone.

My cousin and his father were wounded in an armistice. They were playing–my uncle brought his son out to play in the park and they dropped it on them… on children who were playing. Both of them were wounded. [My cousin] was eight years old. He was wounded so badly that his leg was hanging on a piece of skin, like a small finger. But the luck in the tragedy was that because there was an armistice, surgeons were free since there wasn’t a wave of people coming wounded. When they saw him that he was a child, the six of them came together and said “Let’s do this together.” And together they operated on him and they were able to connect everything back together. But if they weren’t available, they would likely have had to amputate the leg. So that was the only good thing that happened during an armistice, when there weren’t a lot of patients. And what did I go to tell you about my mom, onaj–

The third time that she–

Mhm. That day, we went from university, a beautiful day, really lovely. And really, peaceful, silent, the sun was shining, a wonderful summer day, a breeze blowing. Wonderful. Not too hot. And Sabina and I are passing through this restaurant and now we’re at the exit, we see Sule and his waiters sitting in the garden. And there wasn’t anyone anywhere because it was a workday and it was around 1pm.

It was around 1 o’clock and Sule tells us, “Alright girls, come inside, we can talk a little bit.” And we hung out with him and his waitresses, they invite us to come sit outside in that paradise with them. “Okay, good, we’ll come over [in a little bit].”

We go home to the apartment and my mom, and we’re telling her, “Mama, we’re going here for a little bit.” A thousand times we went to that garden. That was our garden since we were kids, it was safe because it was closed on all sides with other buildings. And because they were big buildings, there wasn’t a chance that someone could see over the building or anything. That was our thinking. That was, to us, safe. We always felt safe there, you know, because it was surrounded by buildings, there was nowhere else we could be “safe.”

We say, “Mama, okay, we’re going, me and Sabina, to drink some coffee with Sule, we won’t be long.” My mom says,

“You’re not going anywhere.”

We say, “Mama, what are you talking about.”

“You’re not going anywhere. You’re came from work, from school. Now go in the kitchen and make grah. Tell Seul that you can’t go anywhere.”

Again, you know, just “You just can’t go.”

Pa, mama, “What’s up? We’re going to drink coffee and then we’ll come back.”

“You can’t.”

You can’t and you can’t and that’s that. I’m mad again and Sabina is mad and we’re both mad. And it was rude, to have to apologize. What’s up with her? Why can’t we go coffee with a guy, with people, and to come back, what does it matter, one hour? You know, we argue, we’re talking, we’re in the kitchen. And so we’re complaining to each other–what’s this gonna do, hey, what are we going to do. Aha, we’ll go to the window that looks into the garden, and we yell down, “Sule, sorry, we’re sorry, onaj, our mom wants us to make lunch, we’ll see you another time.”

“Ok,” he says, “No problem, I’ll see you another time.”

Sabina and I are in the kitchen, we started to work on the grah, you know. Onaj… I’m cutting the carrots. She started to cut the onions. Ma, not even 15 minutes had passed when grenadas– BUMMMMM. They shook all our windows, some even shattered, others didn’t, because in Sarajevo 99% of windows were plastic, from the UNHCR. Some good quality plastic and everything, all those windows cracked, or there weren’t windows, hardly any left. Anyway, we heard the remaining windows falling, you know… the grenades landed in the building somewhere, somewhere close. Everything was shaking, all of those buildings were shaking, and that was… and us two were squatting down on the floor, because you know when one comes there are going to be others.

However, there weren’t any more, there was that one and that was it.

We all gathered around and we’re watching like, “Oh my god, where did they fall.” People are coming to see where it fell. After a few minutes [Sabina] left to go see. Eh, In the garden, there’s five chairs. And Sule, on that day sat, on these inside chairs where Sabina and I always liked to sit. On those exact chairs. Something about them was so nice to us, they’re in the corner, soaking in the sunshine, it wasn’t cold, but you’d get a little bit of a breeze. And because we were in war, everyone was constantly going in the basement, and then your soul was just– ugh, to catch that sun a little bit was so nice. And we were really liked to sit there. And that day, Sule was sitting in that exact spot. When he heard that we weren’t coming, that we weren’t going to be drinking a coffee, they went back to deal with some obligations at the restaurant. And Sule left [the garden] to walk to the restaurant, and the barista was standing in the door when that grenade fell.

It fell right next to that chair. That chair, where we would always sit.

It fell on that concrete and the concrete just blossomed (gestures). And no one was injured, but the detonation threw the barista, who was standing in the doorway, it threw him inside. And he couldn’t hear right for three or four days in one of his ears. Those detonations can do that to you, but then it passes after a little bit of time. Onaj… if we went to get coffee, we wouldn’t be alive.

“Mama how did you know?” That was a first for us.

“I don’t know. Don’t ask me anything, something told me that I couldn’t let you guys go and for you guys to make grah. I don’t know.” She said, “Something told me to not let you go.”

And from then on we always asked, “Mama can we go?”

“Ah, I don’t know my Yasmina, Sabina, I don’t know can you go? Pa, go, what are we going to do.”

But for those three times, when it was dangerous, it was no and no. No explanation, no nothing. And she never explained anything to us. I don’t think she hid anything from us, she could have told us because we wouldn’t tell anyone or say anything because that was “weird,” maybe someone would have called her a “witch,” or, I don’t know. “Psychic or whatever.” That was between us, we never told anyone besides the people that we were really close with. Because someone would say, “Your mom is a babaroga or witch or whatever.” She wasn’t, but she did have some feeling.

The last feeling that she had? She had a feeling she was going to die. That’s also interesting… I’ll tell you this too, it’s not a long story.

She died in February two thousand… 2004.

And, in November, December, three months before that she was visiting one of her sisters in Bihać. And Bihać is famous for the river Una. My aunt [mom’s sister] says, “We’re passing over the bridge and walking. And… She stopped and turned to me to say, ‘My Fato, this is the last time that we’ll walk across this bridge, you and me.”

And she was healthy, at that point. My aunt laughs. Fata says, “I look at her, I say, pa, Hedija, what’s with you? Why’d you say that? What kind of words are those? What last trip?”

“Something’s just telling me. Nešto mi išareti.” That means something gave her a sign. “Something is telling me that we’re not going to be here together walking over this bridge again.”

My aunt says, “Ah, joj, Okay, fool, what are you talking about? Don’t play. What are you talking about? You live healthy, nothing bothers you, and you and I will be together many more times.”

She came home, and her stomach disease started in December. And in January, she had an operation, and then she started to recover and then in the middle of February, she died. She had a tumor, but she had Stage IV uterine cancer, and she had a chance to go to chemotherapy, but she didn’t want to do that because she was already exhausted. They said… she lost a lot of weight and she said to Fata, “ I’m not going to do that, I don’t want to suffer anymore.”

And my aunt was forceful, “Haj, but you could live with us longer.”

“I’m not going to, I’m not going to Fata, don’t make me. Let me go.”

And so that’s… somehow I watched her and how God took her, that he shortened her agony. I was so upset that I couldn’t see her. My middle sister got to see her in December, she was still good. The severity of her problems still wasn’t really known. At that point, she didn’t have that operation but her stomach hurt. And so she went to visit her and to see some of her grandchildren. But, you can see in photos that she’s sick, that… that she’s in pain. She was so thin. And so when my aunt says, “She said to me, ‘My Fata, this is the last time we’ll be strolling like this.” And she says, “That was the last time.“

So I think it was that. And that my mom had those… some kind of abilities.

[Long pause].

During the war, what was a typical day like? What’d you eat? How did you enjoy yourself? What did you do?

Oh my god, what’d we eat?

Typically

It’s funny...Grah, rice, humanitarian konzerva. My cat didn’t even want to eat konzerva. That humanitarian meat, it was so gross… we’d open it and give it to Piljko and Piljko wouldn’t even smell it. It was funny.

Piljko ate other ridiculous things, he drank milk, and he wouldn’t even try that. Gross, gross food. You’d get that meat, and it was so gross, but what are you going to do? You don’t have anything to eat.

Later, we found out that they took their old stock that was expired and–that’s what they sent us. And then, we didn’t eat anything, what are you gonna eat? Grah, rice, pasta.

And the saddest was that when you were in the basement and the kids were playing. Oh my god, “You remember watermelon? And do you remember bananas? And you remember–” it’s funny, they played “memory.” “Do you remember the color of eggplant?” They’d laugh, it’s funny that that was a game for them. Ono, one of those tragic things you hear and listen to how they’d play “Memory.” How things looked and how they tasted.

As far as what we did for the whole day… nothing really, nothing. Surviving. Literally nothing.

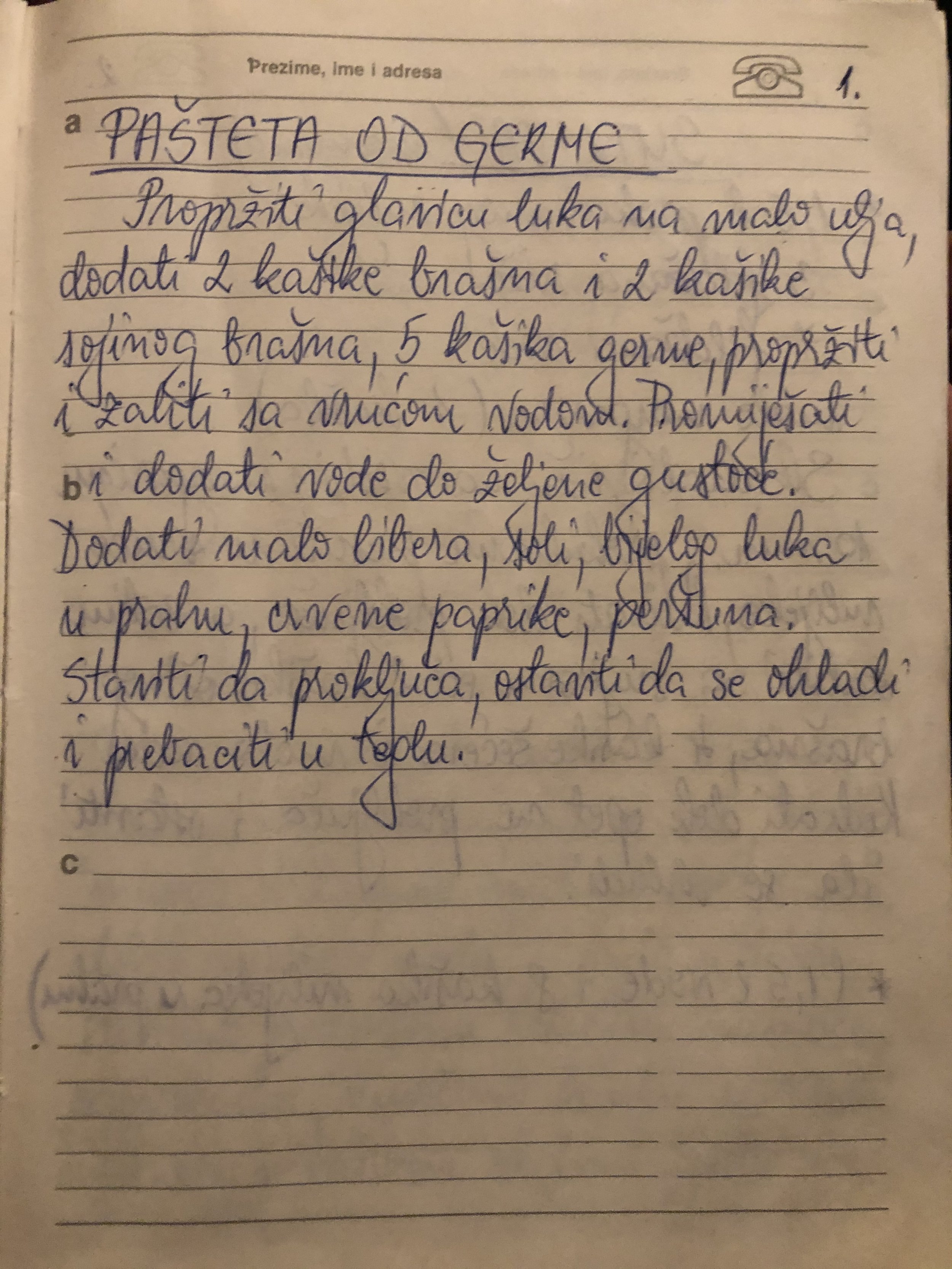

Wartime recipes from Anonymous’s personal diary that she kept in 1993. Recipes include Pašteta od Germe (yeast paste), Zaljer, Pogoča (a traditional bread), šosoko od krompira (potato dumplings).

Pa, you guys went to university, right?

It was so stressful, it was horrible, grenades are non-stop falling on you. I just have to tell you– how we got so used to it. That when we fled to Zagreb, onaj… grenades were falling there, and these people– we were in Zagreb when they started bombing it– we were living with some people, and we didn’t want to stay in a dangerous situation where they could get arrested or something because us staying with them was a illegal and we had a visa for three months. Three months. And we were not supposed to be there when they started shelling Zagreb, but because our papers expired before we could leave and because we’re good and respectable people, we didn’t want to stay with [our family friends], even though they really opened the door for us, they fed us, they took us in, they let us call our parents for free–That’s a big sevap. I don’t know if you’ve heard the word sevap, when someone does something good and asks for nothing in return. That’s sevap. And, onaj… uh, what did I want to say…

Zagreb– when they were bombing the city and how you adjusted to everything

Adjusted to what?

All the bombings.

You get used to the grenades. We even lived in that terror in Croatia too, onaj… [our hosts] had two rooms that they rented, one to me and Enis, and one to another guy from Sarajevo, Dubravko. I knew him from Grbavica. Then, when the grenades were falling, none really where we were, we were playing Uno (cards). The neighbors, this guy and this girl, came over, we were on the floor, we, you know, our apartment door was open, we’re on the floor, playing cards.

They’re yelling, “Come, come with us! Did you hear siren? Did you hear the siren? We’re going and we have a bunker underground, come on, come on! Come with us so we can all hide.” [Laughs].

We were laughing in their face. We say, “We’re not going to the basement for two or three grenades.” [Laughs]. You don’t go to the basement for two or three grenades. That’s when you would go to work. Everything would be functioning normally. We go to the basement when there are hundreds of grenades falling, because then you feel like, “Oh I could actually die,” and-and-a that decision to go to the basement is risky. And then that you could die.

But, you figured out that if you’re destined to, you’ll find yourself in the basement if you think– but you can't’ be in the basement non-stop. We were really in the basement all the time at first. And then it’s just so icky– you become so depressed, you need sunshine, you need to move. You can’t sit for the entire day. For you to see how I slept? You put together four chairs, wooden ones, and then I’d lay on them and sleep like that. And wood is so hard, and I was skinny, and haa— and again you fall asleep, grenades are falling, hundreds and hundreds.

Oh my God it was so many grenades… It was so many, it was so bad. And we’d say to them, “We’re not going down there for a couple of grenades.” They weren’t falling anymore and even they were… eto, you just so desensitized. Absolutely you are and that’s not… and you fled, and now I hear that there’s three grenades in Houston, now, [laughs], I would immediately go and save myself, if they started falling here.

But after four years of non-stop grenades, then…

And after that non-stop, then for you, two or three falling…

One day, my mom and I were making burek [laughs]--What a coincidence, The BUREK Initiative, [laughs]. Anyway, my mom and I are making burek, and you know when you enfold the dough and you start, what we say, kacaš where you’re putting the meat on the dough before you fold the dough around it.Now you need to wait a certain amount of time to let it dry a little bit, but not too dry and now that’s very time consuming and sensitive, time sensitive. And when we, my mom and I, are at work on that when grenades started to fall. They’re falling on the hill beside us. We [laughs] are working outside, and immediately you hear a tree explode on the hill (the hill isn’t far from us).

Maybe a couple minutes walking. Then… two grenades, BOOM! BOOM! My mom and I look out the window, you know when it’s that close, maybe the next one they send would fall on us. I say, “Mama, do we want to [go to the basement]?” My mom says, “Pa, I don’t know.” I say, “Ah okay, let’s not so that this pita doesn’t dry out, we can finish this first.” [Laughs].

And we continued work and they were still falling, really close–maybe a five minute walk away, that’s really close. If we weren’t in the middle of making burek, we would ordinarily go to the hallway. The hallway was an enclosed space, so you could go in the hallway and the grenade would need to pass all the way through the window and through the room and through the wall to kill you. That needs to be a really direct shot, and then you move so you’re not directly exposed. But we didn’t move because we wouldn’t be directly exposed anyway, so “Okay, we’re making the pita.” And by that point we were already in real panic.

You get used to it, people can get used to anything. It was awful. I’ll tell you this, when we’re talking about dark humor in hard times– people really just need to laugh. My sister and I heard from our good friend, he was a doctor and a professor at the Medical Faculty in Sarajevo, Mirsad… I forgot his last number. Onaj… he was wounded. And onaj… because Sabina was a student at his faculty and I had my own obligations there, we wanted to visit him. We read that it was a minor enough wound, that it wasn’t anything extreme, so we went to go visit him. Visitation hours were at 1 o’clock PM. We went a little bit earlier. And so we’re with him, we’re standing next to him, when grenades start falling.

And where the grenades were falling, they’re falling on the entrance where people came to visit, where people are waiting to come see patients. And of course someone was killed there. They targeted the entrance on purpose when there were visiting hours. When people were waiting to come see patients. Imagine that– they figured that out too. They knew everything. They had their own people who would tell them where, who, and what was going on and where they should target, where they would hit someone. A lot of it wasn’t random, it was purposely planned for a specific time. Luckily we weren’t waiting there, and Sabina had her coat with her credentials, she was able to pass through without a problem and I was with her. The grenades were close by, and Mirso tells us, “Go to the hallway onaj ‘don’t worry about me’ whatever happens, happens, go to the hallway.” That way we avoided them while the grenades were falling. And he’s lying down, some shrapnel hit him somewhere on the head, nothing bad he recovered pretty fast.

Now, it’s ‘funny,’ now we’re waiting in the hallway, wondering if it will happen again, since usually they sent a few rounds. And they sent those two, and we’re waiting there when- and this was the sound of the grenades, I don’t know if anyone has ever described it to you. [coughs] You hear fyuuuuuu and then BOOM. And if you hear that fyuuuuu, you’re OK–it won’t hit you. The problem is when you don’t hear that sound because it’s not flying over you, but near you and when you hear the boom that’s when it hits you. You’re the landing point.

And so we’re waiting in that hallway and a lot of people who were wounded came out, only those who couldn’t get up stayed lying down in the beds. We heard from his room, through the window, the fyuuuu sound was coming through the window and that scared us, you know. And then you’re waiting. And nothing, there’s no boom at the end. There’s a woman who was in the corner by the window and said [smiles] “Is that you again, motherf*cker, you’re messing with us again?” An older woman [smiles] talking to this young guy, about 20 years ago, disabled from an ugly wound, a young soldier, across from Mirsad. He liked to make fun of everything. He would poke fun at her, provoke her, scare her.

“Was that you?” She would say “You again?” And he would laugh, “It wasn’t me!” Or, this is even funnier, he says “it’s this disabled guy over.” And the he didn’t have his leg below the knees. He says “it wasn’t me it was this invalid here.”

Humor. Totally black humor I mean it was so funny to all of us at that time. Now it’s not funny to me at all. Because I recovered from all that. But at that point it was so funny. He says “it wasn’t me, it was this invalid here,” pointing to another guy. It’s not as funny for me now as it was back then. [Laughing].

[Laughing].

Was- was there someone really helped you during the war?

[Sighs] Yes.

Who?

Uhhh there was plenty of help. Ovaj, in Sarajevo when we were chasing papers– That’s why I want to be anonymous [smiles] because –

–If you say something you don’t want to include, we can take out that information later, in editing–

-- Yes yes yes, aha… Because we onaj–

Let me tell you about this first wh-why, how we left Sarajevo. Then I’ll tell you who helped us.

How did it come to leave Sarajevo? It was summer. Enis and I were sitting in front of the refugee apartment, the building, he had on some black sandals and one zipper broke on the side. And he’s looking at that zipper and is thinking whether he’ll have the money to fix the sandals by next year. So you’re thinking… You have no money, you’re that poor. Because nobody’s making money. You were only getting humanitarian food and you were living off of that and you have what you have. And he’s thinking whether he will have money next year to fix those sandals. We would patch up everything and when you patch everything up and everything gets old.

I wrote an organization to buy some jeans and two shirts, he bought me fur boots. Oh my God–the way I spent the first winter? Since everything was left behind in Grbavica, I didn’t have any winter clothes. Imagine that!

Anyway, what did I want to say? I’m all over the place. My God, I’m so sorry… What was I saying, about Enis?

So we’re looking at those sandals, we decided, “We need to get out of here. We have to get out of here, we have to make something of our lives.” Three years had passed. No one can see the end. No one could see the end (but it ended within a year after we left).

Now we’re thinking, “How are we going to get our papers?”

I was working in the Red Cross and I had a good job. I was a good worker. I go to ask the director who was my tetak, uncle, and I explain my situation. I say “I want for Enis and I to get out of here, so we can save ourselves. We spent three years in here onaj… could you approve for a business trip to Zagreb?’

If I had some reason to go on a business trip then I could get a visa for between one and three months. He approved this for me without any problem. I will always be thankful to him for that. That he signed it and I got it uhh… That approval from the Red Cross, like I was going on a business trip to Zagreb. And Enis asked the same of his own director that he worked for. What kind of work did he have, how come he didn’t need to go to the army? Because he had a car he used the car to drive for that bizarre firm. Anyway, with that, they hired him as a driver and he drove them wherever they needed to go, wherever that director and deputy went, he would drive them around for work. That way he avoided serving in the army. And anyway, then he asked them too. He explained that we would get married, that we would get out to save ourselves from this, to start some normal life and he also gave him approval.

And that way we got married. There was never uhhh a plan for us to get married ahead of time, you know, just dating but it was like “We can’t get out of here as boyfriend and girlfriend, we’ll get married.”

It wouldn’t be okay or normal at all. And–-we were already dating for a year… wait we started dating in April 1993 and we got out in December 1994, so a year and a half.

My uncle helped me and him with those papers and that, My papers were for Jasmina Alagic, my maiden name and his papers were under his name. Now, we’re traveling together and onaj… of course no one says anything to anyone and that’s, like, “Shut up, we’re husband and wife.” No one knew anything– we made sure that no one knew that on this trip.

Then the Croatian army stopped us somewhere around Mostar and they were checking our papers. It was like, um, like a traffic check point. Inside there was a table, phone, and big window, so you can see the people inside, they were all wearing some uniforms. And that was the most stressful–when they were controlling us. We were in the back of the bus, like the last two seats, most of the people in the bus were women and children and they were quickly going from one to the other, quickly, quickly, quickly. They came to us, they checked my papers and give them back to me. They take Enis’s papers, they’re looking, looking, and then they look at him, and again they’re reading, reading, and then look at him again [smiles].

And in the end, after five minutes of checking, the one who took his papers says “Excuse me, I have to take a phone call.” And he takes his papers and goes outside. He goes out of the bus and into that room with the phone and we see that he’s calling and talking on the phone. [Deep inhale]

“Oh my God.” I say, “Enis if they take you off the bus I’m going too. Just so you know.”

“If they take you off I’m not staying. You and me.”

And he says “ok.”

And he comes back after 10 minutes-- that was awful–he comes toward us, and now you don’t know what’s waiting for you.

“Here you go.” He gives him back the papers, turns around, and leaves. I can’t describe the feeling to you at all. I’m sweating all over when I think about it. That was so awful. He could have easily taken him and, I don’t know… it swallows you in the dark. Who he called, what they talked about, we have no idea. He called someone, talked with someone, the Croatian guard, and gave him back the papers and we passed. Phew.

Then, someone else who helped us?

When we were leaving Sarajevo, through the tunnel–we spent half a year trying to get the papers to pass through the tunnel. They were impossible to get. And when we got those visas, we were chasing them down, we were trying to get them and then we got it - then the night before our departure, we heard, the day before or a few days before, we heard that they figured out something new- oh I stressed myself out with this, that they were looking for an ‘extra’ document that you need to have from the military to pass through the tunnel. And that was the newest thing. No one needed to have it and suddenly they introduced it, you know?

So after half a year of us chasing down those papers…the kind of bureaucracy we had… such is the bureaucracy everywhere, in all of Yugoslavia. Anyway… we came to the tunnel. We’re waiting.

“No, you can’t pass, you don’t have that document so you can’t.”

And so, we go back. We had– my husband’s best man, from the wedding, he gave us the address of someone who lived in Dobrinja. He also gave us the address of some friend on the other side [of the tunnel], in Sokolović Kolonija, that’s where you come out [from the tunnel]. And because we were waiting, no one was letting us pass through. They’d say, “Curfew at 10:00pm.” We decided to go to this guy in Dobrinja, and then in the morning as soon as curfew is over we can try again. So we went to their door, knocking, never seen them before in our lives, but they were friends of our friend, and they took us in. They fed us beans [smiles] and bread, they gave us a place to sleep, warm, nice… it was winter, December, snowing. Onaj… we warmed up, slept, and when we woke up at 4:00 in the morning, we thanked them and went to the tunnel again.

They say we’re missing something. They’re not letting anyone who doesn’t have that paper through. And I’m standing there and looking and I see a man that I know.

I say, “Enis, this is a friend of my relative Azra.” She was mean, but she was in his circle and we often hung out at parties, at hang-outs, at festivities. And we saw each other there [at the tunnel]. I say, “Let’s go ask him, we know each other well.”

And I’m calling him, I just can’t remember his name. But I know him well, we’re friends, not just, like, acquaintances. I tell him, “We have all of our papers but we don’t have the one you need from the military, could we pass?”

“Go ahead.” He says, “Go call Enis, I’ll let you through.”

I call Enis, “Let’s go” I say “He’s letting us through.”

And then Denis, Enis’s brother, this is funny—Denis wanted to carry a heavier bag, Enis wanted to carry a lighter one, and I wanted to carry the lightest bag and a purse [smiles]. Denis was in great shape, he was in the military, so he was carrying two bags, Enis was carrying what I was supposed to carry, and I was just carrying two small purses. And with just those two bags, I was dying going through that tunnel. It was 800 meters, 900 meters. And I’m tall, with the two of them, going through this very small, small tunnel, for most part in this position [hunches over, scrunches shoulders, laughs]. Some parts are just so low, some are a little higher. How long does it take to go 900 meters? I’m not sure, 20 minutes, maybe.

Can you take any breaks?

Oh, no! How would you take breaks? Everyone is passing through, everyone is trying to get uh through it, to the free side. So we’re going, going. I’m all happy, telling Enis everything, “Oh it’s great that they let us pass, we’ll make it through!”

And Denis is telling us, “Don’t celebrate too far in advance.”

Enis says “Don’t celebrate anything in advance. He let us through, who knows–”

Enis was older and more mature, seven years older than me. But I was really happy to be getting through. We came out to the other side, and they put us in this room. You wanna know how big that room was?

I don’t know what to compare it to… a little bit bigger… like your bathroom.

Whoa…

30 people in a room the size of your bathroom [to daughter].

[Daughter] That’s not possible.

Oh it’s possible! Like sardines! Literally. Really! Enis was a witness. Such a small room- I think I can say it was like that so he can confirm.

[Daughter] Yeah, he was there.

Such a small room.

They put all of us there and say, “Stay here until we decide what to do with you. Do you have the papers from the military?”

“No one has those papers.”

Then he cursed and said…I was white as a ghost… out of all the people who were there…I was so… Denis and Enis tell me that I was white as a ghost. I was like…about to lose consciousness. So they brought me a chair, but there were a lot of older people– why me? Who was young? 24 years old. They brought me a chair to sit because they say that- that I would [gestures falling over]. And onaj, they tell us, “Give us your papers.” We give Enis’s passport, my passport, Denis… Denis didn’t have to give anything because he was a soldier. So he went in and out with no problem. And onaj…

And they returned Enis’s passport, my passport. But they took all of our other papers from us in that room, and the guy, the soldier, left through the tunnel, goes all the way back, and he just said to us, “Go wherever you want, but your papers are here on this side.”

So then you’d have to go back. And now I say, “Enis, my dear, I can’t go back. I won’t make it. I fell down in the middle–” and there were enough people there in that tunnel who knew they’d die, they couldn’t stand that whole trip again. Enis said, “I can’t stand anymore, I need to take a break so I could go back, if we’re going to go back.” Denis said to Enis, “Okay, okay,” he said, “I’m going to show our– I’m going to our– I’m going to try and get these papers for us just so we can leave from here.”

Denis says, “Listen, don’t go anywhere, don’t you dare go back, I will try to get back your passport. Stay put.” I will come back again. And like that he went– he went with us once, then he went back two times, and then when he came back the third time, he brought the passport to Enis.

How he managed to get Enis’s passport? He was leaving and he said to the soldiers, “You took my passport on the other side, can I have it back?” And because he and Enis are twins and look alike, the soldier asked “What’s your name?” “Enis.” And he found Enis’s passport and he got it like that, because he said he was Enis they didn’t take anything from him because he was a soldier. And he came to us immediately so that means he passed through the tunnel four times and he tells us, “Hey here is Enis’s passport.” But Enis and I never wanted to split up.

Enis said, “You should go immediately, I’ll give Jasmina the passport and she will come with you.” He and I were talking about that because we saw people who were ‘separate’ like that and they weren’t able to get together for years and marriages broke up like that. So we never wanted to split up-- together no matter what happens. Enis said “Thank you brother, but I won’t leave [my wife]. We will wait together to see what we can do about her passport.”

“Listen,” he tells us. “I’m good with Jovan Divijak.” That was a Serbian general in our army and Denis had done a favor for him once.

“I’m going to look for him. I’ll look for him, I’ll ask him”’ However when he went to go look for him, he couldn’t find him. He went somewhere for work and would come back in a couple of days. They told him that he would come in a few days, “I’ll go and ask for him,”

And then, the soldiers told us that we could leave [the tunnel]. Okay.

And we leave from there and we’re standing in this one place where they organize the whole group. And now Enis wants to leave and go call those people in Sokolic Kolonija, where our friends gave us their same address in case we needed it– We really had a lot of help.

We were heading over to those–again we had never met them before, but we told them that we were friends with the best man from our wedding, who they knew, and they took us in. I will never forget how they took us in, that was when it was freezing, no power, no water, no phone, no nothing, and to come there–warm, nice, couches with lambskin covers so it was warm, nice, we parked ourselves there.

The woman made dinner with potatoes and onions, chicken with potatoes, and salad, and she brought out a cake for us. That was like came to heaven, everything we ate there–we hadn’t eaten chicken in years, not even potatoes, not even salad. We’re eating and we have this ‘unbelievable feeling, I don’t know how to describe it to you, how much we had missed normal food!

By God, a few days later, Denis was there with my passport.

“How did you do it?!”

“You should have seen how great it was,” he said. [Smiles]

“How?”

He says, “I went to him and he took me in. We’re good with each other. I asked him, ‘Do you remember when you said you would do me a favor?’ He says he remembers. I sa, ‘Here’s my situation–they have all their papers, but they don’t have the approval from the military, they have a visa for the trip, could you please go get her passport so I can bring it to them?’ He says that he can.”

They sat in a car and came to Dobrinja. When Jovan Divjak went out of the car everyone stood up, you know, saluting the general. Denis says, “The two of us went in where there was some guard. And he just told him to find the passport of [interviewee]. And they found that passport and just gave it to him.” Denis says, “Jovan just gave it to me and said to bring it to you.” [Smiles].

And Denis went through the tunnel again to bring us the passport. So General Jovan Divjak h-h-h-helped us too. And [deep breath] then we continued our trip.

We come to Tarčin in Tarčin then we go along the road because the sniper is shooting. We didn’t even hear the shooting– we felt it, there’s just a feeling of “how can a sniper shoot you.” Awful.

And then when we passed that, it was like, “Okay, one level down, next level?” Like it was some game [laughs], you know. First the passport, then you’re there, next level: sniper. Now, next level– Tarčin. In Tarčin, there was snow. There was a couple of meters of snow that had fallen, you couldn’t go into Tarčin or out of Tarčin. Next level. What are we going to do now?

But again, someone helped– these people from Sokolović Kolonije gave us that address for people in Tarčin if we ever needed it, and my God, we find these people– Jaoo, they were such fine people if you could see them, really such fine people. They also had some cattle, but in the house, it was so clear and nice and after working around the animals, those, those boots had gotten so dirty, but in the house everything was like brand new, really clean, I haven’t seen a cleaner house. Like you were getting it from a magazine, everything was white– white oven, white everything, everything was clean and they were, everyone should reach that level of cleanliness. The woman fed us– I don’t even know their name. I just told them that we got their information from these friends and they feed us and she gave us a bed and that pillow and blankets, it was all so nice. It was the most important thing that we were warm because we were coming from cold Sarajevo. It was just so nice for me to be warm and to enjoy the warmth.

The next day, we woke up to a little snow and we spent one more night. Then we went off to Split and then from Split to Zagreb. When were came to Zagreb, we went with our friend Saša’s parents, and we were there with them, I think, three months until our visa expired.

When it started to expire, we were looking for an apartment it was.. it very interesting.

You call someone on the phone, you ask you see something in the newspaper announcements for apartments, then you’re trying to rent the apartment for a month, and on the phone they ask you “Sorry, what’s your nationality?” and “Excuse me, what’s your nationality?”

They’d ask that on the phone, “Ah, sorry but what is your nationality?” And my Enis would say, “Ahah, what do you need?” [laughs].

Like you guys could be whatever they need you to be.

What do you need us to be? What’s the point of that question in the first place?

“What do you need? “If you’re not Croat, then…”

Okay. “Yeah, yeah, yeah.” We hung up. What are you going to do? You can’t say that you’re a Croat when you’re not. [Laughs]. But Enis was so good, “What do you need,” pa, rent us an apartment, we were lucky because we… our friends– cousins, I think one of Enis’s cousins, she lived in that apartment and then she moved somewhere else and then she gave us those people’s numbers, so we went and lived in that apartment. But everyone was asking you what your nationality was. Horrible.

When you guys were in Zagreb, that was that story about bread happened, right? Hleb and kruh?

Ah yes. So we, Enis and I, went to go buy bread. Hleb. Or for them, kruh. I enter the store, Enis was waiting outside. I’m trying to buy bread in that bakery. I’m entering and I say to the woman, I say to her, “Could you give me some that hleb?” And she says, “We don’t have hleb here.” And I’m looking– there’s a lot of bread behind her. How do they not have bread? What’s happening? My people, “Oh god, am I in the twilight zone? What’s going on?”

When she saw that I was confused by her, she called her colleague in another room and they joked, “Hey come see this chick looking for hleb.” And when I saw that, “Oh.” I realized they wouldn’t give me bread unless I said kruh. And in that moment, Enis entered the store to see what was going on, how they didn’t want to give me bread because I didn’t say kruh, but that I’d rather say hleb– they want me to say kruh. And I’m leaving [without any bread], and now we’re going to a different place that was self-service.

And now Enis is going to ask. And we’re approaching, I’m holding his hand and now Enis says, “Excuse me, could I have that hleb [bread]?” And I start nudging him and I say “It’s not hleb it’s kruh!”

And the woman goes, “Of course, of course, I understand you, I’m a refugee from Banja Luka, where are you from?” [Laughs]. We say “We’re from Sarajevo,” and, ya know.

Oh my God, that woman surely understood us, we could go everyday “Can we buy hleb or kruh” it didn’t matter.

When did the war end for you? Was there a specific moment when you felt that it was over?

When I came to America. Why? Because even in Zagreb there were problems. Those first three months were awesome for me. Because we had a three month visa. And then we needed to move apartments. We didn’t need to but we didn’t want to put our hosts in a dangerous situation– they took care of us and received us well, for us to live for free and they fed us, whatever we needed– detergent, they’d buy– they were really lovely, and then I’d help them however I could– cooking, cleaning the house, and stuff, to repay them.

But, when we moved to the second apartment… Everyone else knows when something is going to happen. Because, the Minister of Defense, I don’t know his name now, I forgot, he was the first neighbor of the people with whom we were staying. And the day before grenades started falling in Zagreb, our host, Marija, she saw how people were lowering their blinds on their windows. And it was a normal work day, it wasn’t a vacation day or off day or anything, their kids went to school, it was absolutely not clear to her why they were lowering their blinds. Our people only lower their blinds when they’re going on a trip. When they’re going somewhere. And it really wasn’t clear to her why people were lowering their blinds on a nice day, you know, they don’t have ‘em in the house. She noticed that because it was the first window next to hers. It was the next day that those grenades were falling on Zagreb.

She knew that the Minister of Defense knew that there would be grenades and that he pulled out his family until that passed. That’s when she realized. And then we found another apartment, because every question for us was “What’s your nationality?” Hmmm… “What do you need?”

Zagreb wasn’t the end at all, just like a new phase…

Because we were illegal. And when the grenades were first falling, that was just the war trudging on. The war had come for us, there were no grenades in Zagreb before we came [laughs]. And then after those grenades, our papers expired because embassy staff couldn’t come to Zagreb to interview us for our American visas. They weren’t going to risk it. Rather, we had to go to the interviews in Varaždin. We traveled by bus. And that stress them from this interview? Oh my God, that was awful. I’ll tell you this just so that you understand how stressful it really was–Onaj, I won’t go long, just a little bit, this part.

I had six interviews in total that all lasted a really long time. They went into detail. I guess, I don’t know, they were that long so that they could catch me in a lie or something I suppose.

In that last interview– I had an identification card from Grbavica. And that was my proof that I was a refugee–because I couldn’t return to Grbavica since they took that part of the city, and I was a refugee. And that Enis couldn’t go back to Livno because there were Croats there and it wasn’t possible to travel, it wasn’t safe to travel there, but we went with my story, not with his story.

So the interview we had in Varaždin… that was the worst one for me. Some American officer came in, someone else was translating what I was saying. And she was really, really serious and, uhh…she tried to make the situation more intense than it was and I was already nervous. And she was very strict with her questions. Whatever. She said to me, “Aha, you’re from Grbavica?” I nodded. She said, “Please, get that map and put it in front of me. Can you find the building that you were living in?”

I’m looking at this map, nothing. Nothing is familiar to me. Why can’t I recognize anything? You can imagine how worried I am that I can’t even find the street that I lived on, not the city, nothing is familiar to me. I’m trying to look at this map, I’m worried, now I don’t know… if I can’t find my building and they’re not going to let me go. I’m thinking they’re not believing that I was from Grbavica, even though my picture and my address and everything said so.

I’m searching this map for a good 10 minutes. Jojj… Oh my God, I’m sweating 100 times over, I’m searching, I’m searching. At the end, I looked at her, and I tell her “Nothing here is familiar to me, I don’t know what to tell you, I can’t find the building that I lived in.” She says, “Oh, that’s okay, we didn’t give you a map of Grbavica. [Long silence].

Seriously?

Mhm. “We didn’t give you a real map.”

Why? To see if I was from there. And if I wasn’t from there, I would have told them “Oh, that’s my building.” You see? That kind of game.

I guess that makes sense but there had to be another way to… that wasn’t so mean. That’s just mean.

You think? After the war, which you survived everything, to give you a map and you’re sweating and watching and searching and to tell her “I can’t find it.” “Ah, that’s okay, that’s the wrong map.”

Pa, I don’t know what to say.

Pa, you don’t need to say anything. Maybe now it’s a little more clear to you why this interview [for The BUREK Initiative] was so stressful for me. [Laughing]. Nothing personal. [Laughing]. Nothing personal. [Laughing]. Just saying. Everything I went through, there were other things in other interviews. Eh! Next, you know, what stress I had? Good that I –

That’s really stressful, that’s really like a different level. Ridiculous.

Pa, crazy. Really, to make you crazy. And and that Twilight Zone, c’mon– she’s like the one that said we have no hleb like… what?!

And now you’re like, “Is this hleb or kruh.” [Laughing]. That’s the next test. What’s after that?

Ah, I forgot to tell you this.

We’re traveling, Enis and I, on the tram [laughing] and I tell Enis, “Enis, we’re getting off at the next crossroads.” And the entire tram in that moment turns and looks at me because I said the word, “raskrsnica.” Because that’s a Serbian word, I didn’t say, “raskrižje.” That was awful, they’re looking at you, but their views are so full of hatred…you feel them on you. And I look up and all at once they’re all watching me and I’m just ignoring them, but you feel all of them looking at you. You feel it. Especially when you’re an empath– you feel..

From then on we started speaking quietly, but we had one more very stressful episode. We went every day to eat from the student canteen [sighs]. We were lucky because we heard that a lot of students get coupons for food but they don’t eat there, they sold those coupons to refugees for money [laughs], so that they get money to have fun and they go cook something, they eat at home, and use that money for going out, to have fun.

That was well known among people, stories were circulating, go there to that canteen, stand where they give the coupons, and just ask, there would always be someone who would want to sell you coupons for money. We did the same thing. We went to buy those coupons and that was great food, there’s a picture… that’s a picture from the canteen . The food was great, tasty, I think they cooked really well. It wasn’t the typical food from a dining hall, you know that it doesn’t even have taste– I work in a school, so kids who eat that food… it’s sad, it’s awful. I can’t try what the kids eat. But their food tasted really good, excellent.

Anonymous and her husband at the university canteen.

One day, Enis and I were coming and we wanted to go into the canteen, through the main entrance, the dining hall, when these two men stood in front and asked for our documents. Onaj everyone who was coming in. And we understood that they were verifying something, but we weren’t sure what. We didn’t leave but we stopped, a bit farther back to look if they were actually asking for documents. We were standing, he and I were talking, and we peek out of the corner of our eye and we see that he’s really stopping everyone and asking for their documents, ID card–you needed it to eat there.

We just turned around and left, we continued coming there, but that day they were controlling it. And one day, we were waiting in line inside. We went inside and were waiting, you know, in that line. When a man comes over and passes everyone, one by one. I got so scared, I told Enis that I really think that the man will check everyone at the end of the line. Because why would he pass by all of us? I immediately had those thoughts.

You’re in fear because you’re illegal.

And the man went by us, and passed, and he went somewhere, but I was dying for those few minutes until I saw that he wouldn’t be checking us. [Exhales, sighs in relief]. Because if they get you, they immediately put you in a truck and send you back to Bosnia. Imagine that fear. Believe me that those four months that I was in Zagreb illegally were worse than when I was in Sarajevo. Mentally.

You weren’t free. Not suffering—Sarajevo was more suffering—but Zagreb was mental. You’re free one moment and you’re not free the next. That feeling… that you’re always in danger of them getting you and sending you back. You understand? So you’re still not free. You’re still in the hands of… Others. You’re not in control of your life.

And then when did you come to America?

Let me tell you about another interesting thing first.

My sister got her papers for Vancouver, to get her doctorate, and her husband had to wait to sort out some of his papers. So he became our roommate. We still went to the cafeteria to eat, but we were always dying of fear when getting there and coming back, we even started buying extra, so we would bring home a bowl and pile on for ourselves and go every second or every third day, so that we wouldn’t risk being on the street as much. And that was a good idea, you know, we would heat it up for ourselves in our apartment and that was okay. But Muhamed was without his papers. He had approval to be there but his visa had expired. Yes, that happened to him too. And onaj- this is really, really interesting– the kind of luck that man had. He [sighs] came onaj… aha– the Canadians gave him some papers with his picture showing that he had approval to go to Canada, to Vancouver, because his wife was there, and there was his picture and name, and then he was just waiting for his visa for Canada. He got it the same morning that the police checked him. So he’s coming back with those papers from the Canadian embassy, and the police stop him. He says “if they stopped me on the way there, I wouldn’t have had anything.” He says “but I got it from them and I was going back to our apartment.” He says “He stops me, says, ‘Give me your papers.’ I have a Bosnian passport, my visa expired, but I had those papers, I tell him, ‘I’m waiting for this program.”

The man takes it, looks at it, and he called someone. Talked to someone–okay. And gave his papers back to him and let him go. It was that same morning. Imagine that. And he says, “Imagine that this happened on the way there. I wouldn’t have anything.” But that morning, they had told him to come in so that they could give him his papers. And then he waiting, I don’t know maybe another month.

The universe at work (laughs).

Right? Yeah. That was really cool, that was so cool. The universe, God, Higher power, whatever. He's a really good guy, he's really good guy. Like something helped you. [Laughs]. Something's going somewhere. You’re not going anywhere. So yeah, he- but if we were with him, we didn't have papers at that time. And usually, if we were leaving the apartment, we all three went together all the time. But that morning, we didn’t go.

Enis and I felt– because we realized it that they verified people in some places. And then we were, you know, we were a couple in love, so we walked all the time hand-in-hand or hugging so that we wouldn’t look like refugees [laughs]. If we looked like we were Zagrepčani [Zagreb locals]. [Laughs].

Like if we could look like we lived there, you know? Like we were at home. That we weren’t, ono.. tense, terrified.

You’re under stress every moment, every day, and–

[Laughs], exactly. So yeah, it was like, okay, we figured something out. And that feeling came to an end too. We were hugging– I remember this well– we were at the Zagreb train station. We’re walking on one side and from the other side of the street, two police officers, stopped this couple, [laughs]. The guy has a backpack on his back, she– young, both of them, really like us–they were stopped and they were fine because they were legitimate and had their papers. Enis and I are just watching them over there, from wherever we were, and we got going. I don’t have a point… we were just, one street to the left, a little ahead of them.

From then on, we didn’t go out anymore. [Laughing]. When that couple was stopped for their documents, maybe he had a backpack, but I’m suspicious… I don’t know, he could have been a student. Normal people, young people like that, hugging, they were stopped, and we’re across the street. We just started moving, like, “Okay we’re going away from here.” And then we mainly stayed in the room. And when we got those papers– we were so relieved. Really, we had some ridiculous happiness, to say the least.

Everything would end well but something always gets complicated. The night before our departure from Zagreb, [coughs], the friends that we had met, they used to call us from time to time to come see them. To sit and drink coffee with them, to watch TV, to talk, and they lived in Zagreb, ono, in Sandžaklije, which is where we met. Until then, I didn’t know anybody from Sandžaklija, I-I don’t know how we met them. But we were hanging out with them before we left. This was the last night before the trip.

The police came for this guy from Sandžaklija, a Muslim, that lived in Zagreb. The police came for him. I have no idea why. No one ever came before, his wife said, and no one came after. And he traveled for business a lot.

So he wouldn’t be in the house for a couple of days, then come and be there, and then leave. And she would always call us when he came back so we could sit together. On that last night, she suggested to us that we bring our things over to them and that we spent the night over there, so that in the morning we would be closer to the bus station, because they lived near the bus station. And then we wouldn’t be late or have any kind of problem, their apartment was really close to the station. We thought, “Okay, fine, let’s do that.” We get to their apartment, and at some point in the night we’re watching TV, maybe around 11pm… [whispering]... someone knocks on the door, knocks loudly, [louder], knocking, knocking, we were scared–what is this?!

“Police! Open up!”

[Laughs]. And in the morning we were leaving. What are the police going to do to me? With that– you can imagine the feelings.

The woman opens the door..“Are you [Last name omitted]?”

“Is this the apartment of [name omitted]?”

“Yes it is.”

“Where’s your husband?”

“On a business trip.”

“Okay.”

And Enis and I are standing there just… waiting [laughs]. They say to us “Give us your papers.” We have our papers ready. We, at that point, had some kind of ridiculous papers from the refugee program. Like papers with pictures stapled in the corner. You don’t have anything else or a passport or anything. [Laughing], you don’t need a passport from Sarajevo to Zagreb. But, for America, you just needed these ridiculous papers that said, “Approved refugees to go.” These fools needed these papers and are searching for papers, now they’re complicating things before the trip.

Imagine: you’re finally leaving tomorrow. And the police come to you, knocking on your door, after you’ve been avoiding the police for four months, the night before your trip. That’s happening to you.

Thankfully they didn’t ask us anything else. They just asked for her husband. And she was terrified, saying, “What is this? Why are you coming for my husband?”