Raika A., 46

Herceg Novi, Montenegro

“At that point I was thinking, “I don't want to live like this.” I looked at other people around me, I looked at doctors - hungry. Engineers - hungry. A taxi driver had a PhD in Biology… I don't want this life. I do not want to live in such a society. And what I had... I was young, I had nothing to lose. No dogs, no machetes, no children, no husband, nothing. What do I have to lose? Just your life.”

Interview originally conducted in BCS.

What’s your name? Where are you from? Where did you grow up?

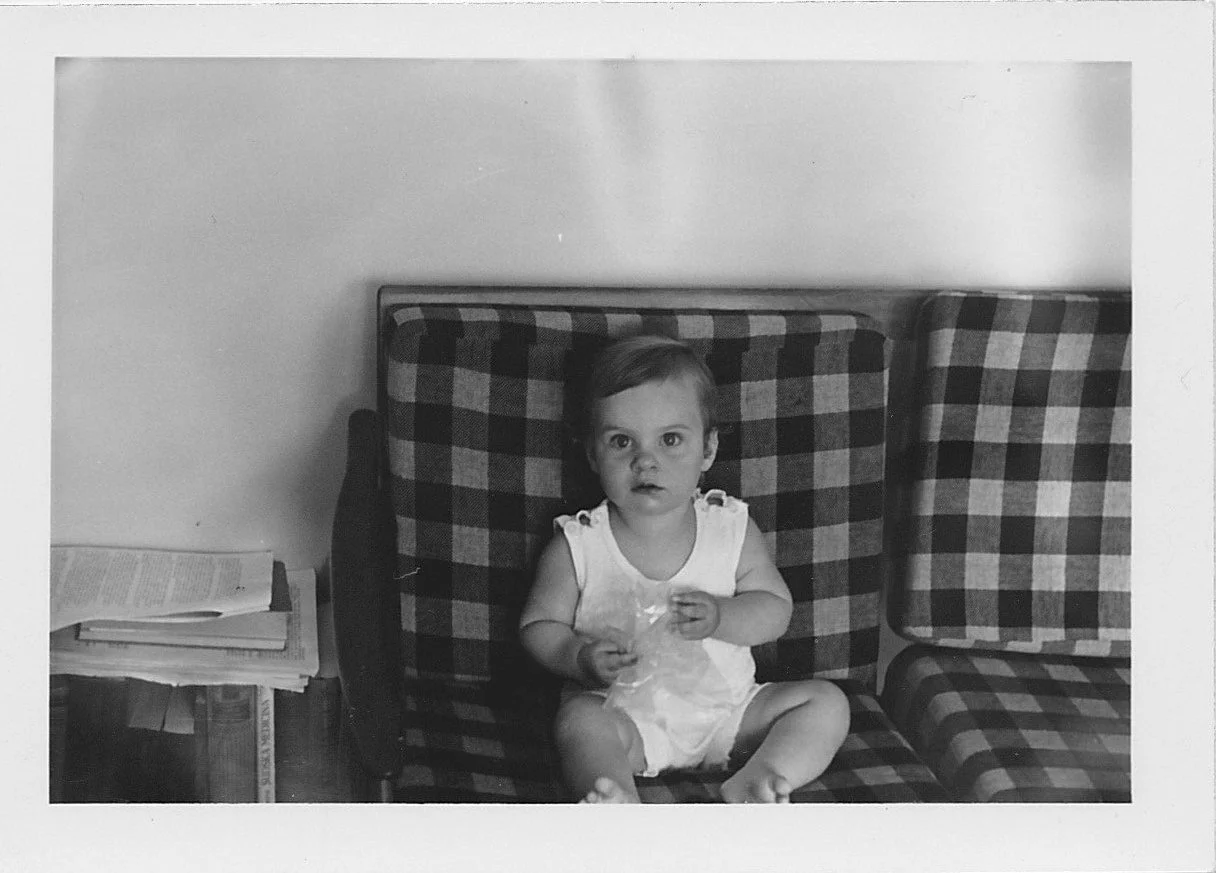

So, my name is Rajka A. I was born in Dubrovnik, 1975 in Yugoslavia. I was born in Dubrovnik because Herceg-Novi, where I grew up, didn’t have a hospital so women would normally go to Dubrovnik to give birth. So that’s why I was born in Croatia… which came in handy later in my life [laughs].

I grew up in Herceg-Novi, it is a small place on the coast in Montenegro, 11km from the border with Croatia [laughs]. Life – I had one beautiful childhood. When I think about my childhood, I feel- I feel sorrow that my children – won’t have a childhood like I did. It was so… innocent and protected and free and safe and that… that [sense of] freedom has stayed in my memory the most. Freedom to be what I want, freedom to go where I want to, f-freedom of everything. And it was somehow humble but beautiful. We didn’t have much, didn’t have toys, (we made toys ourselves), we didn’t have any “brands.” I had one tennis shoes for dry weather and one shoes for rain and that was normal and everybody lived like that. We hung out and it wasn’t important who your mom is nor who your dad is nor how much money you have, nothing. We only enjoyed one another. And me as a child, when I compare it to my children, I had a lot of responsibility...to help my parent and to take my little sister to kindergarten and to go to school alone, and to study alone, and to finish my responsibilities, and somehow – even though I was a child, somehow- I remember we were somehow responsible, responsible for ourselves, responsible for our duties.

That childhood of mine was so beautiful, especially in summer time… we would go to the beach every day, there was no “summer camp” or anything [like that]. Parents would go work, children would go to the beach, they would swim all day there, go home for lunch, then in the afternoon go to the beach again and that’s how we hung out. It was nice.

I remember one time-- it really stuck with me-- I was maybe 12 years old. I remember, I was going home from the beach and I was taking the stairs (Herceg-Novi has so many stairs, wherever you go you’re just going up-and-down). And so, I thought to myself: How happy I am… that I was born in this place, in this time. And I had some, like some inside “joy” because I am there where I am and because I am who I am. And it was all good like that- uhm… it was nice… until uhm 1992 [inhale] when [pause] war in Yugoslavia started. Is there something that- that you’re asking me extra, that I didn’t say?

Oh no, it’s, it was great, how—

-- why, you want more details about how my life was? You want more in depth—

-- Well yeah, you can say what you want to and—

And the war was getting closer...that’s how the tensions grew and it was becoming more and more important, you know-- Are you a Croat? Are you a Serb? Are you a Bosnian? Are you orthodox catholic? Are you Muslim? Are you catholic? Everything--all of that started to be taken into consideration and all of that was what was important. It wasn’t important anymore that we were friends, that we were brothers and sisters, it was important who was who. And then some bullying started happening in school... mocking you if you are a Serb, if you are a Croat, if you are a catholic.

Because my parents were, by some new measures, from a mixed marriage, they were getting some unpleasant calls – anonymous – on the phone. Um… but they were somehow brave and persistent and didn’t pay much attention and they didn’t tell us kids any of that, I found all of that later on.

In ‘92 my dad decided to start his own business and to go to Germany to some “technology fair” where he would buy equipment for his new business. We sat down in the car and decided to stop by in Zagreb to see my grandma and my aunt and everybody, and then to- to continue for Minhen. And I remember [deep breath] we got to her place and we were watching TV one night, a day before we were supposed to continue our trip to Germany, and we were watching some… “civil arrest” in Slovenia.

My dad wasn’t sure if we should continue our trip to Germany over Slovenia or to go through Hungary because he didn’t know what would happen. However... when we were [in Germany], it was actually really nice. But, when we were supposed to go back [home], the war in Croatia started. And we weren’t able to go back to Montenegro through Croatia. And-and... even though that was very saddening, I was very happy that I got to see my grandma and my “family” before the war started because I didn’t see them six years after that.

We returned home through Italy. It was summer, I remember, and in October, the war started for real. Like we felt that it was there and that-that it would last and that it would be horrible.

Where were you in October?

We went home to Herceg-Novi. And in October--how did the war start for me then for real?

Because I lived near the border, a uh, one part of Croatian territory was the Yugoslavia’s army and it was somehow- maybe 10 kilometers air line ahead (above??) Herceg-Novi.., JNA was there and they were throwing bombs, the missiles-- I don’t know, how do you say that na našem, raketa, možda, on Dubrovnik and Cavtat.

And I remember how my house shook from those detonations and-and-and me and uh dad were staring on a balcony and looking towards- towards Prevlaci, its that part of Croatia, JNA and how the purple light glows- from how they’re throwing those uhm- those rackets fell and- and I found that very, somehow...awful. Um, some type of sadness. And the entire city was in the dark and there wasn’t light and there was only that purple- [cries, laughs through cries]... that purple light. My sister was very scared and she went into the house and cried and wasn’t able to calm down... my mom wasn’t there, she went on a business trip in London.

That’s how we were there and we weren’t able to get in contact with her. [Cries, sniffling].

-- you can take a break if you need to, you can take a break.

I’m sorry this is very difficult for me—

-- it is, it is.

-- because I never think about this. Please forgive me [laughter].

Take a break if you need to and however long you need—

-- and uh...I remember when we went to school the next day--sorry, my memories are a bit disconnected because I can’t remember some things even if I want to, somehow my brain throws it out, I guess-- I remember that time we were going to school.

And I remember that our teacher told us uhm- I think I remember only the traumatic moments – we were scared that there would be a response from Croatia’s side and that they would aim at us. And, uh... the teacher told us that if we heard the [bomb] sirens that we should flee the classroom right away and get out of the school into woods. Because--my school was very close to a forest--and he said: “Run into the forest and please, everybody.

“Please don’t go in groups because if bombs goes off, I want the smallest number of you possible to die.” [cries, laughs through tears]

And I... I remember that. It was so like… I didn’t know what to [do]. I was waiting for the siren to start the entire day. But, thank God, nothing ever fell on Montenegro.

Then, the next moment I remember, and what was also traumatic for me, was when the Yugoslavian army started to enter Croatia. My house was right next to the Adriatic highway and those huge tanks were passing by my house... every house shook, they were crushing asphalt with those continuous tracks and [they] destroyed that road and the soldiers were yelling there and waving some flags. People were literally hiding in houses because that was nothing--because we had to live.

We were living near Konavle, [it was] directly on the other side of the border with Croatia. In Croatia and Konavle, people that were living there gravitated toward Herceg-Novi. They were going to our schools, worked in Herceg-Novi, their agricultural products were sold in our markets, so we had this connected life and it didn’t feel like they were from Croatia. We--it was one country, that was normal. Dubrovnik was too far away for them and they gravitated towards us. And in my head, I remembered those beautiful Konavle grandmothers that wore their ethnic clothes when they would come to the market to sell and they were so pretty and they had some traditional jewelry... I- I- I still remember them like some dolls, beautiful like that. And then, when those tanks were passing by, I somehow thought about them, and-and why is this happening? What would we do? I had some guilt...I don’t even know. Even though I was a child, I felt the injustice.

And then ... I remember when the army ended up there in Konavle-- they actually went there-- but the people of Konavle fled a long time ago, they didn't find the people of Konavle there. They went there to steal, to...I don't know… and then when they came back, they also passed by my house and then that's all they stole, from free shops, at the airport, and what not, like that with tanks were thrown around, it was just such a desperate sight. I don't know… somehow how we collapsed like that.

I mean, I understand that those people who went there are not from Herceg Novi. People from Herceg-Novi did not go to plunder the people of Konavle, I think those were some people from some other villages and some other cities who did not know who the people of Konavle were or how life was with them and that.

[But anyway], back to ... And then during the war, to go back, after that attack of the JNA attack on Dubrovnik and when the army withdrew and all, then there was a truce to say there was no more shooting. We didn't hear that. But then, there was an economic crisis, a huge one. We had some hyperinflation where everything lost value. The dinars were in the billions, money worth nothing.

My mom — my mom at the time was the Chief of Physical Therapy at the hospital. I remember that, for her entire monthly salary, she bought one can of mashed tomatoes. That was inflation. That poverty was a disaster. There was nothing in the shops, everything was empty, no vegetables, no fruit, no bread, no meat, nothing. Nothing.

Then, refugees had already started coming from Bosnia to our city. They brought with them that EU aid, which were some kind of meat cans and I don't know what was inside and they kept getting it and they sold it to buy something else they needed. Then my mom bought those cans of meat and made who knows what out of it. She made up some recipes [laughs]. I think I’ve eaten potatoes in all the ways it can be prepared [laughs]. I wasn't hungry, I don't remember being hungry, my parents saved a lot before the war and all of their savings were in German marks, so when the war came, they nibbled from that money and bought food from it.

But I remember that there were hungry people because my mother brought lunch to a doctor colleague at work because he was hungry, he had nothing to eat, and she would prepare it and take it to him so that he would have something to eat. It was very hard, people committed suicide because they had nothing to eat, uh... it was one state of despair.

We didn't have anything... I didn't have any money, I was in high school then.

I remember my friends, the five of us, when school was over and we didn’t want to go home, we went to hang out and sit in cafe. And then the five of us would collect fifty-cents, that was one espresso cafe, and then the five of us would sit at a table, and that cafe would be in the middle of the table, and we'd like a little sip-sip-sip until we drink that one coffee. And it was a kind of "treat" that we had.

And then after that inflation misery, we somehow stabilized a little later, but it brought huge poverty. I would say 90% of people who had nothing and worked for some poor money, they lived with the help of relatives. Montenegro, Serbia, the whole of Yugoslavia, was a country that gave birth to immigrants, so people went abroad en masse in the 60's now sent people [still in Yugoslavia] money, I think the whole ex-YU after the war lived off the help of families who went to America, Germany, Switzerland, and they just sent it so people would have something to eat.

And the war lasted the whole time...I remember, ’96, the war continued in Croatia. There was the exodus of Serbs from Croatia, and I was already in Belgrade at the university at that time. And that poverty continued there, people were...People had nothing, there was no gasoline for city traffic. People fell out of the bus because they couldn't get everyone to the station, because instead of, say, 50 buses passing in an hour, five would pass. I also went to college, in the middle of winter, we sat on those wooden benches in the amphitheater. There was no heating, I’m sitting in a jacket, I’m sitting on a pillow I carried from home with someone else, my legs are freezing, you sit for three hours, you listen to lectures, and it [was like] ice entered in [your] bones [laughs].

I’d be waiting for the bus for two hours to go home, I come home, take off my shoes, my toes are blue, it's cold [laughs]. I remember, I didn't even have functional heating in the room I rented out, where I lived, I slept in a winter jacket with a hood and two more quilts because there was no heating.

And in Belgrade it is terribly cold in winter. But again, on the other hand, all that poverty...I think what kept me alive [and] not be a chronically depressed person, are those friendships. Those gatherings, those people I met. We would just meet at houses, sip coffee, hang out, talk, sing with a guitar, that was the way. We didn't have the money to go to cafes or to clubs or anything. And when I think of that time, even though I'm telling you in detail now, I don't-I don't think of that poverty, I don't think of any horror of the war, I just think of those beautiful friendships and those beautiful hangouts...

I was in Serbia, in Belgrade at that time, and the situation was getting worse. A worse financial situation... we went back to a new cycle, there was a shortage of food in the shops. And this one time, I remember that when I heard somewhere that sugar came [in stock], I ran like crazy to the one in the store [that had sugar], to stand in line. "Oh my God, the sugar came!” And-and everything was so miserable, miserable. I remember, there were presidential elections, and-and they were stolen. And then—

What year was that?

I think that was in...'98., '97. I can’t remember. It's all messed up in my head.

And [anyway] the huge demonstrations started. The students demonstrated. I demonstrated for three months, every day in ice, in the rain, I missed semesters, I missed the exams. I forgot about college and I went to demonstrations every day, every day, from morning to night. And that lasted for three months. Without any major results… we didn’t oust Milosevic.

And then one day, workers from the interior, from factories, came to Belgrade to protest to remove Milosevic. Protesters were beaten by the police every day. And day they came was awful. I remember, they threw tear gas at us and tear gas is a disaster... it burns everything inside [of you]. It catches fire. And uh, I was fast enough, I didn't-I never felt a baton hitting my back, [laughs] but-but... it was that day. Thanks to those workers, who came from those factories [and] from the interior, the police decided to stand with the people and stopped beating us. Milosevic stepped down from power. It was a big day.

I have so many pictures from that day with my friends and this one we were so excited and so happy. I don't know even felt that joy when I gave birth [laughs]. I finally felt that I might have a future. That I might also have some kind of life that my parents had. Even though until then, I felt like “There's no way, this is misery,” [now I felt] “I'm going to live and that’s it." I felt like it was going to be that day when life would really begin. We were all so excited.

However...we elected a new president. He was eloquent, intelligent, educated, he spoke foreign languages, he was loved by Europe (which is very important because they need to give us money to build ourselves out of our misery). However, it didn't take long... he was assassinated and he was ... "done". And those terrible feelings reappeared behind me...some visible patterns in government that reminded me of exactly what [life] was before the war and I felt...that day… that my life in Yugoslavia was over for me. I knew that I had nothing more to search for in Serbia or Montenegro, and I told my parents: "I don’t want to live here. I will dig with my hands and feet to [get to] any country, Western Europe, America, anywhere, anywhere. I don't want to live here.” It's just- as if for me life was over there, I said “I can't rot here anymore.” I'm done. I had no "expectations” for myself there. I was lucky enough to uh win the greencard lottery and come to live in America.

And when I say—

-- That was 2000?–

-- October 5, yes. But-- when I say "happiness", [it’s] happiness in the sense that everything is relative... it means happiness that I was given the opportunity in my life to be something else, to do something else. But, really, my happiness would be if I stayed in a country where the people I know are, where the culture I know is, the language I speak and where...where I feel at home. That would be happiness. So, for me, coming here was like an "escape." And I never, ever in my life thought that I would ever go back there. And nothing can make me...without saying anything, who knows what can happen in life, that something happens to my parents, God forbid , but would I ever decide to go and live there? Never.

Although this [America] is not my country, and it will never be my country--I do not understand people here or culture or anything, nothing--But I am better with these foreign people than with my people there. Because I see my children and I see that they have hope for them, they are Americans, they will live nicely here, and they have all those opportunities that I think in a normal country people should have. And that's how I experience it. And I like to send them there [to Yugoslavia], I like them to understand the culture, I like them to understand the language because it makes them rich—

-- So they have that connection.

Yes, but I would never [want them to live in Yugoslavia]. And now I... whether they will go to with this international relations or political science or decide to do some kind of "research" there, I will be supportive, but to tell them, "Go live there"? No. I like to go there and when I go there I am reminded of everything I miss here, but I am also reminded of why I am here.

Did I answer the question?

Yes! You--

-- If it’s too much, cut it out. If its too much detailed, cut it out—

-- Oh no, no, no, I just have a few questions.

When you did you leave Herceg-Novi for Belgrade?

I left for Belgrade in 1994. I lived my entire life in Herceg-Novi.

Okay. Was there a specific moment when you- when war started for you? When it was like “Wow, this is happening” –

-- Yes it was that day with the city-wide blackout and when they were shooting Croatia from the cannons and I was watching how those cannons...how my house is shaking and at that moment I realized that Yugoslavia is done. Yugoslavia is broken and I knew that nobody will ever patch it, that...that was that. And then I saw the tanks that were passing by my house… then it was clear to me.

I was 16 when it happened and I don't remember many things from that time, but that day? I really remember that day. I remember my sister who was in such a trauma, she cried so much and we couldn't calm her down, and with that… I don't know how to explain...I can't say that I was afraid. I was not afraid. But I felt... there was that kind of uncertainty, of what would happen tomorrow. Will I go to school tomorrow? Will I be alive tomorrow? Will my dad have to go to war? Will my mom have to go to war?

My mother was a doctor and in the hospital in Herceg-Novi where she worked, they dragged the Serbian army from Bosnia and Croatia to [help] patch up the wounded. And those were the people who fought with the Croats there. My mother is Croatian and my mother speaks Croatian. My mom went to work every day in fear if one of her patients heard her speak it, she was going to have an incident, or God forbid, that she...

-- Da.

So she...she is a doctor and she will help everyone and there is no prejudice, whoever comes to her, she will treat them. And uhm my dad--we were lucky, my dad worked at telecom and he worked at and his role was to stay in town. So, I was lucky that my parents were not mobilized.

My mother was at the hospital, but she worked at the local hospital again, so my parents didn't have to go to war. But my mother's sister's son, who was in Zagreb, he was mobilized and he went to war on the Croatian side. We were terribly afraid for him. We didn't know if he would come back alive, and um… many of his comrades from the frontline committed suicide. And my aunt was terribly scared for him because he had been sitting in a dark room for a year and he didn't want to talk to anyone and they were scared when he came back from the war… I thought... at the same time I thought, while he was at war, that my dad could have been mobilized and that they could’ve shot at each other. Um...that thought was the one- catastrophic to me. Fortunately, my cousin came back. He survived. He somehow got out of that depression and I didn't really, personally, lose anyone in the war. And I think it's the same happiness. Um- what-What else did you want to ask? A sub-question?

The question was, was there a specific mo-

-- That, yeah that moment. Everybody said: “Just act normal.” Like, life goes on, and then I say, the next day when I came to school, then our teacher told us to-to run in fo- [laughs] fores-

Every day was...we lived day to day. Today is like this, how will tomorrow be? Nobody knows. And that was...I think that-- as awful as it was, I think that it gave me some...“advantage” in m- in my life now. Because I am uhm very “comfortable” to live in uncertainty. It doesn’t give me any anxiety that is… okay? [laughs] Whatever happens – happens. [laughs]

When we talk about the war in Yugoslavia, people often say that the war came out of nowhere-- that it was a huge shock. When you think about it now, can you see any signs of the war?

Yes, it didn’t come out of nowhere. No, because we were one country--One communist country where there was no divide noticeable among people. If you were religious, you were religious in your house. It's not public--whatever you do, you do at your house. For example, when I was born in 1975 "nationality" on my birth certificate-- says "Yugoslav"-- Because my parents raised me to be "Yugoslav." No one ever told me - "You are a Montenegrin." Or "You are a Croat." I mean, I'm Yugoslav.

So, today, when someone asks me: "What is your ethnicity?,” I do not know what to say--Yugoslavia is no more, but I am not Montenegrin. And then I say, "I grew up in Montenegro, but I'm not Montenegrin." I don't know if you understand... I'm kind of a man without ... "nationality". Without "ethnicity", I don't know... it was once and it is no more. And it said Yugoslav, but when my sister was born, three years later, that Yugoslavia no longer existed. But, [it] had "republican citizenship." So you couldn't write "Yugoslav" [as an ethnicity] anymore, you had to write either "Montenegrin", or "Serb" or ... I don't know. So, you see when you look, why has that changed? So even then, those were "incremental changes.” Things--

Right--

Things, you know...why did we all of a sudden have a “state?” That was ‘78. They started creating rifts in between politicians. Now each republic had its own President of the Communsit Party, as they were already called. And they started denying responsibility, [saying] “We in Belgrade aren’t going to determine what they’re going to do in Croatia.” And then they started, through the media-- media is really powerful tool-- to plant the seeds of division.

And then it started like that. It started that we were no longer a “we”... it started with “We’re Croatian,” Serbian, Bosnian, etc. To slowly put people...slowly spooning out people’s brains so that they start noticing those differences. All it once-- from “brothers and sisters” to…[division].

For me, it seemed like all at once everyone knew that my mom was Croatian and that I was baptized in a Catholic church and that my mom was a Catholic and that… it all suddenly became known and suddenly became important.

And so it started. It takes time to create that kind of hate toward others in people’s psychology. And then when that turns into aggression toward others, then it’s already okay in our heads. Because they “deserve” that, you know? That created one of the conditions to create war.

It didn’t start all at once. We were conditioned for that.

[For example], we were all okay with one Croat being bombed. Because the media built [them] up in our heads like our enemies, so then it was totally okay for you to start shelling grenades there.

My parents pretended that they didn't see it. Like many in Yugoslavia... that is why many people say that war came suddenly. Because people pretended not to see it. But that all existed. Because no one could have thought that something like that could happen to our country. Nobody could have imagined it with their own heads. And then it was like, for example, it was such a normal day in Sarajevo, people were at the market, doing their job, when suddenly someone started shooting at them. And they say, "Suddenly it happened." But if you look a little closer, you see that it wasn’t sudden. That it was preparing and preparing and I believe uhm-m that they- we were not a small country, I believe it was all funded from abroad, we could not slaughter ourselves alone.

And nobody, I believe, no one I know from there says that their life is better now than during Yugoslavia. Nobody. And nothing is better. And for me, the aftermath was worse than the war. Because after the war, that devastation remains.

I also forgot to tell you that I was in Belgrade, I don't know if you're interested in that, during the NATO bombing.

Yes.

Are you interested in that story or not?

Yes, yes, tell me.

It was also something no one could have imagined. Because we were one European country, no one could have imagined that now someone would start planting bombs on one European country for no reason. We did not attack anyone, we did not threaten anyone. And I remember I was in Belgrade, and on the day before the bombing started, everyone started fleeing Belgrade. You couldn't find a train ticket or a plane ticket at the bus stops ... There was ... like an outflow of people from Belgrade, an outflow. I remember calling my dad now, he said, 'Dad, everyone's running, should I?' He says to me, 'Don't, sit there.' ", He says:" Who will bomb Europe?”, you know. And he tells me: "Sit there. " I say, "But Dad, everyone's leaving!" He says, "No, no, no, don't do anything, sit there."

And the next day, I went to college, there were normal lectures, I had lectures until late in the evening. I remember I got on the tram to go home and suddenly the sirens started. The whole city...sirens began. Blackout. And the driver opened the [tram] door, and one woman said, "It's just an exercise." And then the driver opened the door and said, "They said on the radio that if we heard sirens it was real." And all city traffic, everything... everything stopped. And all the [tram] doors opened and the people just started flooding into the streets. I also remembered that I had a colleague from college who lived in some military building, and that there was a basement there. And she was the closest to me from that tram. I ran to her, and she was already there and took me to their basement. I was afraid to go, I couldn't get myself to go… right then I discovered that I was actually terribly claustrophobic and couldn't be in the basement and I started to have that paranoia of the bombs hitting the house and the walls would be piling up on top of me and how I would slowly die for days. And then I decided not to be in the basement.

I went out in front of that building and I sat on the stairs and in that darkness… I sat alone and listened to those rockets pass by. They make a whistling sound when they fly. And so in that darkness I only saw that kind of red light-- When it passed. If the bomb was coming toward you, you would not see that red light.

And, uh… and so the days went by, and I decided one day to go to that apartment where I lived. I ran out of money, I ran out of food [laughs]. I decided to somehow get on the bus and go home because I didn’t know what I was going to do here now. And in the apartment building where I was staying, my apartment was on the ninth floor, a rocket landed on the building. But it did not explode. Luckily. Otherwise, I don't know if there would be anything left of me. It crashed… I was watching from the window how the roof was broken and it was standing inside.

I decided uh to go home[to Herceg Novi] and get on the bus.., I traveled for days.. Because, every time I enter an area where sirens were going off, the [bus] driver stops. He could not drive under alert. And then s-sleep on the bus, sit in the bus, you never get anywhere. And my family didn't know [where I was], the phone didn't work, they didn't have any contact with me, I didn't tell them I was [coming] home, but since I knew that I would just go hungry, I had to hurry.

And I remember when I came home, my mother- was running towards me, she was crying: "We thought you were dead. That you were gone." I said, "Why mom?" And they were watching CNN via satellite as Belgrade burned.

And after that, when I went back to school, in Belgrade, there was that stolen election and demonstrations started. After the war everything was "devastated" after the bombing. And those demonstrations took down Milosevic… and then a new President came and then he was killed and, uh… that's it. That's my life in the war.

And the most unfortunate thing for me is that as teenager during those years, I uh planned to travel with my friends, to go to Europe, to see the world. My country was under sanctions for those eight years of that youthful life and I did not travel anywhere, there was no money, now… it’s like someone stole those years from me. And somehow it seems to me when I moved here, that I wanted to live those st-stolen years again. It’s like my whole life has been shifted by that eight year lag. That I live now… like I'm 8 years younger. [Laughs]. I don't know if what I'm saying makes sense. [laughs]. When I came here [to America], I wanted to travel and my then-boyfriend, current-husband, we we traveled everywhere.

I wanted to somehow make up for lost time and then I had kids late too and everything is kind of late in my life. Because I guess we all have this need for exploration. You know, when you're young, you want to go everywhere, to see everything, to try everything.

To go back in time -- what was a typical day like during the war?

Yes, well... so I would go to school in the morning-- oh yeah! Refugees started coming to us. In class, we started to get children who were not from Herceg-Novi, [children] who were from Bosnia or wherever, and that it was kind of interesting because when you live in that little place, you grow up with all those same people non-stop. No one comes, no one leaves, we all know each other. And now, all of a sudden these other kids are coming with other habits. I remember we tried to hang out with them, but it was very difficult because, I think, they carried a kind of trauma or suffering that we may not have been able to understand.

And then, social life was very limited. We didn't have the money to go anywhere and I tell you all the time, you might think, “Well, that must have been terribly boring, you must not have done anything.” But we hung out all the time. We sat together and hung out. So there was… there was that charm. That you weren't alone.

When I look back on it, it was a terribly boring and monotonous life because there was nothing--nowhere to go, no concerts, it was like some kind of survival. We survived-- we did not live, we survived. That's how it was. There was nothing. I can't tell you anything specific, except that it’s.. will we eat? Will a bomb drop? And that's it. We didn't have money, no one had any money ... And maybe it was good that no one had it. Then we were all together in that kind of trouble. There for each other. Does that make sense?

Yeah, that does make sense. To fast forward a bit, when you were in Belgrade and when the demonstrations starte, how did you decide get involved?

Well because...that government in Serbia...they were such mobsters. They stole and manipulated everything. So, my mother sends me money, from Herceg-Novi, so that I can live in Belgrade, and pay me money in Montenegro, in a bank held by Serbs, and when I come to the bank, they don't give it to me. They are waiting for inflation and then they buy foreign currency with that money and what not, and then they give me that money four days later when it’s worth half as much as when my mother sent it to me. And they did that to everyone. People received salaries a month late. [There was] no heating, no-no... nothing, no food. People are hungry. And we were in college, like it was such a miserable study. I mean ... There was nothing, and our books were nonsense, no content, no - it was so miserable, poor and sad.

At that point I was thinking, “I don't want to live like this.” I looked at other people around me, I looked at doctors - hungry. Engineers - hungry. A taxi driver had a PhD in Biology… I don't want this life. I do not want to live in such a society. And what I had... I was young, I had nothing to lose. No dogs, no machetes, no children, no husband, nothing. What do I have to lose? Just your life.

And I then went and demonstrated and demonstrated and—

What were demonstrations like?

Raika’s photos from October 6, 2000, the day Milosevic fell.

Well, you know, I didn't want to fight with the police. Firstly, I was a woman. So I demonstrated, but every time a mess with the police started somewhere, I ran away from them. I didn't want to fight with the police.

But, we would all meet, for example, in the square. And there were millions of people, and everyone went, the streets were closed. Everyone goes... holding slogans, banging pans, shouting, yelling ... when you are in that group, you feel some power from that mass of people. We were all one. And there was a grandma next to you and grandpa and older and younger, we were all there, connected by that one idea that we want a better life.

Our people are terribly rich in spirit. And while you are marching with people, people are joking, people are laughing, jokes. It’s all one-one-one positive energy for a better tomorrow. And I went there with my friends and for us it was a normal thing, every day, for three months, rain or shine. Snow? Ice? No. Let's go, let's go, let's go.

And that day, the last day, people from inside set fire to the assembly, stole all the furniture, [laughs]. And I think that only four people were killed that day, which was phenomenal -- I mean, it's not phenomenal that someone was killed, but in such a civil unrest, with four people... it went well.

But after they killed the new prime minister [who came to power after Milosevic]...then I lost everything. You asked, "Would you go back [to Montenegro]?"-- I would never come back. Because I think everything there is the same as before. Nothing has changed. Always someone to hate. And I think it was all hatred again born of poverty. Because people...when you don't have [anything], and not by your own fault, you are looking for someone to blame for your life. And I think that... it was the same then, that there was a basis to create that nationalism and hatred, among people.

When did the war end for you?

For me, I don’t remember a specific day. I think it was...Americans got involved, and it was- I think it was after some Dayton Agreement. I don’t remember those political details. When Americans got involved and they told us “Okay, no more fighting…” and then we listened and [laughs]

But you never had a specific moment when you felt “the war is over now”?

-- No. You know what’s unbelievable? I’ve never felt, to this day, that the war is over. I think of that country like something that is constantly boiling. Constantly brewing. And it just needs somebody throw some new spark and everything will explode again.

Something’s gonna give.

Yeah, I never feel that its some safe place to be. That it’s some country of uh prosperity, some country of progress… always, I think about all of the worse. [Laughs] Not about people. Not about people, about-about life. And that’s not the same.

I go to Montenegro to see my parents. But I don’t feel like I belong there. I don’t feel like that’s.. my country anymore. I think… when Yugoslavia broke up, that stopped being my country. That’s not my country anymore. America is not my country. I am in some type of limbo. I am... I feel that I am a person who doesn’t belong anywhere.And that’s how I feel. And that’s one, very weird… a rather a weird “feeling”.

And I go there just to see… mostly my mom and dad, my aunt from Zagreb comes to Herceg-Novi and we all see each other. And… when I look at her, like- I remember how she was before the war and how it broke her and ruined her, physically and-and then... In fact, when I go there, I don’t feel any “joy”, I feel like somee... like all of the suffering uhm returns. And it’s like- somehow I can’t get free of that negative energy. I don’t know why. But that’s how I feel… I still see that suffering of people and realize that since the war started, that it birthed whole new generation which are now people and parents, that have no memory, no- experience of what it means to live normally.

Yeah.

That they don’t know... they are born in suffering and that’s all they know. And those people can’t be “progressive” and move the country forward. Because they don’t know-- they don’t have anything to look up to. That’s how I see it.

Is there something you want Americans, or any other non-Balkan people, to know about the war?

That’s a difficult question.

I can't answer this question [pause] without telling you...Because Americans don't care about American foreign policy. If we are to speak generally. The Americans do not know where Bosnia is, or where Syria is, or where Iraq is, or where Afghanistan is. These are some distant lands there, where there are some people who have nothing to do with us, who we don't understand, and they "probably deserve what you get." Something like that...I mean...that it is very general. So then it is difficult for me to explain to the Americans what they could have done for the Balkans, for the war, when they know nothing about that war. I mean ... when I tell people here that I am from Serbia, since no one has ever heard of Montenegro, they ask me if it is a "Russian republic". So, in general, of course, people who… I noticed that people who follow "soccer" know more about Yugoslavia than even some who have graduated from medicine, for example. So I talk more about my country with a checkout guy in a grocery store who started telling me about football players more than about someone who is super educated.

As I see it… Since I'm always trying to find some explanation at some much higher point for why, you know, "You did this to me, I did that to you…” I think the whole concept of globalization that started in America. America did it in order to conquer new markets and new resources for the economy, as it must, how do you grow an economY? New technology with new markets, right? And now uh I think that's what happened in Bosnia and Kosovo and that… that we have suffered... that we are victims of this process of globalization... because these ordinary people have no idea about anything. "Wherever the money is."

That it is in their interest, in their interest, to have as many small states as possible in the world, because it is easier to exploit them, and they are too small to survive on their own and will always need help. And when you depend on someone to help you, you are not "free". And I think that the whole process of globalization was that through the exploitation of resources or markets you make them independent of-of- let's say the American economy, which also made the European economy dependent on itself. And then I think, what happened in the Balkans, for example, Americans, if they wanted to, they could have stopped that war. But it suited them to break up that state [Yugoslavia] and then have those little states. It suited them that we hate each other, because if you hate each other so much, you will never be together. And then we were left with those small, unhappy, independent states, which have nothing.

We depend on European bank loans, they dictate to us what they will buy from us, what they won't buy from us. We are in the machine. We have no economic independence. And I think - not even politically - and I think that, through that lack of independence, you always have nothing - you are not an "entity" in itself. You depend on others all the time. And then I think that I can't look at that war "personally," like someone did something to me, or to our people, or someone didn't like Yugoslavia, or I can't look at it that way...I-I understand the globalization scheme and I can understand how we fell into that scheme.

And I can say something to the Americans now, what I would like to-- I have nothing to [laughs] because I understand why it happened! And it's still going on, because that's how capitalism works.

I really don't think that Americans-are sitting here, that they have anything to do with what happened in the Balkans. Or that they can change anything. But I also think that the media here always creates such an atmosphere that an American never experiences the suffering of another nation in which these "interventions" are made. I think that...to let a picture from Syria on CNN, for example of a father holding a dying child in the arms while the house was set on fire behind him, to show it on CNN, I think half the people here would be astonished. Saying, "That’s terrible"and imagining ourselves and how awful it is and how we should stop it.

But, since those pictures are never shown, we think it somewhere far away, to some other people about whom we know nothing ... So there is no empathy for suffering, for the suffering of another people. And I think that maybe for people here, if they really knew and could understand what is happening in countries where there is a war, if they would - develop empathy and then maybe did something... But I can understand why this is not happening, and I don’t blame them. As for what I would say to people in the Balkans…

That’s my next question, [laughs]--

-- I would say to our Balkans: Shame on you for allowing you to quarrel, and to hate yourself, and for being played by these people at the top, for playing their war games, and for ruining a wonderful nation. And we are to blame for ourselves, and that's why we are responsible for fighting each other because they quarreled with us and for allowing us to quarrel. And that's something ... that's up to us, because if we didn't...if we didn't want to beat each other, we wouldn't beat each other. Neither America nor Europe could force us to do that. But we were short-sighted. We had to find someone to blame for the misery we lived in, and when you blame someone else, most easily your neighbor. And during the war I even thought, when I was watching television, watching those conflicts and everything that happened horribly, especially in the territory of Bosnia and Croatia, and then as a young person I thought: “Look how we slaughter and kill each other here, and I have a feeling that Milosevic, Alija, and Tudjman are sitting on Sundays, drinking coffee together and thinking: "Look how we ruined them, we don't give them anything, and they still love us." [through laughter] And that's how I imagined it.

And I should say to the Balkan people, our people: Shame on us. That we ruined our country. Nobody ruined it for us, we ruined it ourselves. We continue to ruin it ourselves. That's how I see it.

I have no one to blame. I don't blame anyone, and what I believe is that most of the Yugoslav people did not hate and did not love but- but- but... kept silent, and looked at the country, while those 10% of bloodthirsty and furious criminals went around killing, a good and fine people hiding under a stone then. And he said nothing.

And- and I think that we...failed there.

[Long pause].

Then, my last question is not not about the war, but about burek-- Do you have- do you have a story about burek? Something you want to- to say?

Ah yes. Burek was in my life since forever. First memories of burek [through laughter] were from my hometown. Where I ate gibanica. Burek is- one meal for which every nation in our Balkan and in esthern Europe has its name… Somebody calls it “pita”, some “gibanica”, some “banica”, some “burek”… at the end, all of that is made in the same way with minor details. So my mom made… gibanica. Which, similarly- and she was the one who made it, that- that’s how I grew up, eating mom’s gibanica. Then when I left home, I went to Belgrade. Where I tried the best burek in the world. I ate burek every day. It was the cheapest food, like a glass of yogurt with burek. And that was my main meal and the best thing was when I go out with friends and when we drink and we get so drunk, there’s nothing better to collect alcohol in your stomach than a good, greasy burek. And then I was living with one old lady that I rented a room from while I was a student, she taught me to make some pies on some-some special, her, way and that I loved extremely. I learned to make those little pies and then when I came to America, I made those pies for Americans that were amazed by it so I was sharing the recipes for burek with American women who continued to make it in their own homes [laughs]. And that’s how I brought burek with me to America.

That’s a great story.

But to- today when I go to Eastern Europe, wherever, that is I think the only food I miss. One good, greasy burek [laughs] and a glass of yoghurt.

So burek is something that definitely connects us.

Yes…

I really like how you thought of that.

Yeah.. thank you, its- I agree… it’s the best food for everything.

For breakfast, for example, I make my way to college, take that burek in bakery on the bus stop, burek and yoghurt and that keeps me going the entire day. I don’t have to eat anything until dinner.

[long pause].

I think that...I think that I think that your generation, my children, will begin to "care". I can imagine, for example, your generation, and younger. That it will be a new generation that simply will not have a belly for war. To them, it will be something "outrageous". And this social media... it connects young people so much that they know... Young people don't watch CNN or MSNBC, they are on social media, on their network they have a completely different vision of the world. And everything. And I don't think your generation and younger will allow further killings. I really have- I really have like this—

-- Feeling?

I really have hope.