Admira M., 34

Sarajevo (Butmir), Bosnia-Herzegovina

“And you’re seeing people wounded, you’re seeing people get shot, or you’re seeing things that bring it home for you. So even if you don’t understand the larger picture of why things are happening, you understand your day is dangerous.”

Interview originally conducted in English.

What’s your name?

My name is Admira M.

Where are you from?

I am from Sarajevo, specifically Butmir, a southern neighborhood in Sarajevo. The oldest in that area, actually.

Tell me about yourself—where did you grow up? What was life like? How did you spend a typical day before the war?

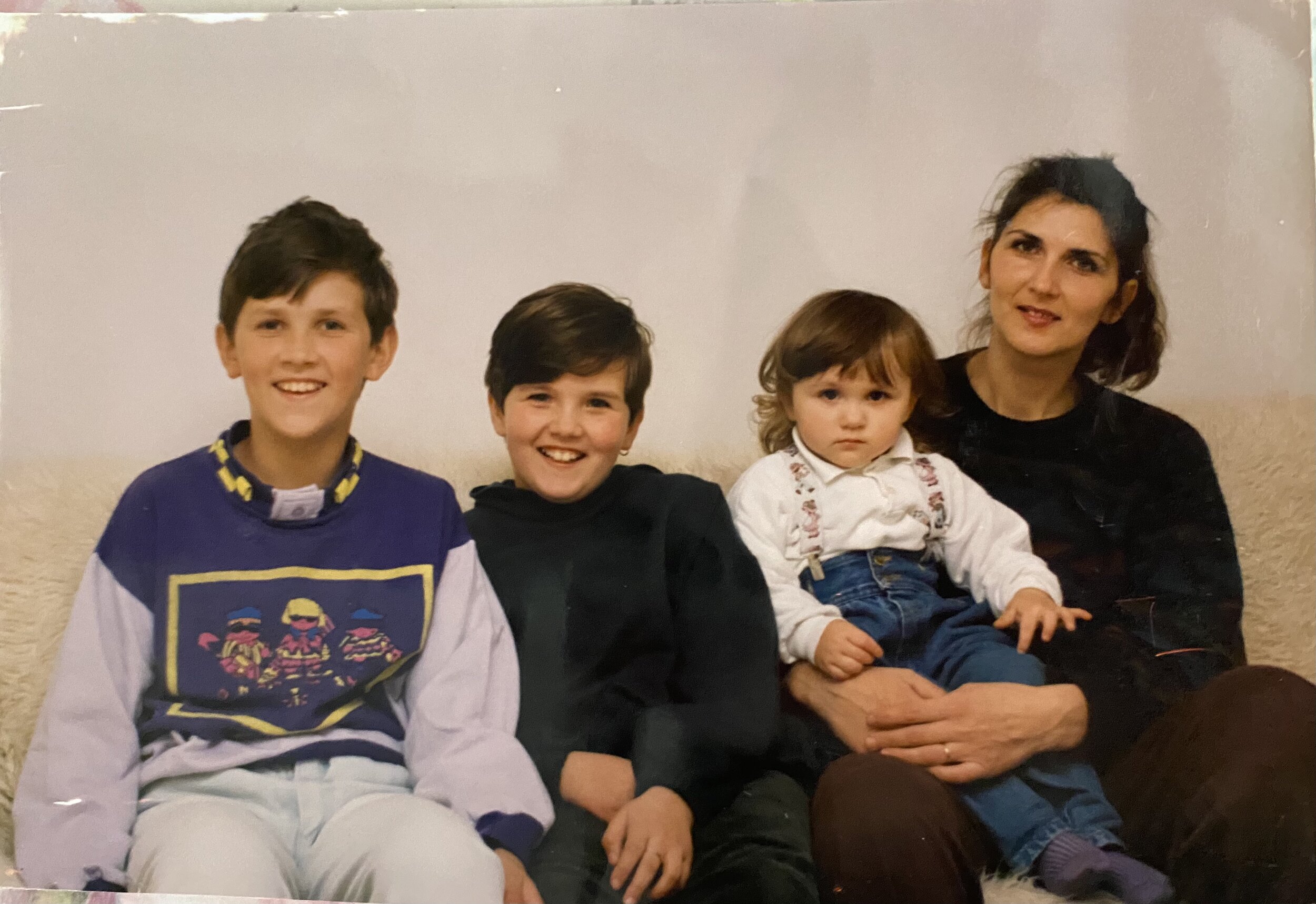

So, I was born in May of ‘86. And, we lived in a multi-story house —which is very common, I think, for our families. I had my aunt on the first floor, my parents and my older brother and I were on the second floor. The first three years of my life I was watched by my mom’s mother, [my] grandmother. I would go [to her house] every day, and I loved her to pieces. She was a very wonderful person.

I think I had a very idyllic childhood. We played a lot outside, we rode bicycles...I was playing usually with my older brother and his friends—I was a big, big tom boy—and we played, like, marbles in the dirt and ran around. And I don’t even know how to say it in actually english, but like we’d, it’s funny that we were talking about that, but we would... hmm. It’s not jumping rope, but we would have elastic essentially and [we] would play games, like [we] would skip elastic and [we] would make shapes out of it, and the girls would do this. When I was three, my parents enrolled us into daycare, and so I went to daycare and it was my average day. Every year we went to Croatia for a month to vacation on the beaches, my parents had good jobs, good salaries, and we were just a really happy, probably average family, with grandparents and aunts and uncles and cousins all around us.

When did the war start for you? Was there a specific moment when you were like, “Okay, this is happening”?

Yeah, interestingly, I don’t know [for] what length of time, [but], I would hear my parents discussing with their friends [and] with family like, “What do you think about the possibility of war?” As a kid, I was about 5 at the time, I remember not really understanding the concept. And the responses they would give to each other were like, “Oh it’s never gonna happen, never gonna happen.”

And then one day—I remember this day so distinctly because again we’re on the second floor of a house that has a underground basement—my dad comes home, he rushes into the house and I think my brother and i were playing in the living room, and he says to my mom,

“Pack, and move into the basement now.”

And that was April of ‘92. And my mom says, “What’s going on? What’s happening?” And he goes, “Yeah, the, četnici, are literally a mile away from the house. You need to get in the basement. And my friend Hajriz saved a gun for me, I have to go pick it up.” (Because there were limited arms available to hand out to soldiers.)

You almost immediately started to hear what we really didn’t notice initially which was the background noises of war. Which is like rolling tanks and grenades exploding. Distant background, but you don’t recognize that sound until you realize what’s going on. As it got closer, it became more distinct. Definitely.

But anyway, we packed up and moved into the basement. A basement that had been a storage space. So we made a makeshift… we put mattresses down to sleep on and we had a wood-burning stove, which we were really lucky to have, but it had mice and crap in it which we needed to clean out. And [we had to] figure out how to… how to live in a space that really wasn’t habitable.

That was, that was that day.

What was life like during the war? What was a typical day? What’d you eat? Did you go to school?

We didn’t, we definitely stopped going to school immediately, everything shut down. With the Sarajevo region, once it got surrounded, you really couldn’t leave your house. You had—If you left—you had to walk between houses, there was a constant threat of shelling if you stepped out into the open streets or areas that could be easily seen from the surrounding hills where the Chetnik army was. Even around us, even though we were a little more south, there was constant shelling. We were south of the airport, which meant that at least we weren’t cut off completely from all access to resources, to some food, but it was unsafe to leave.

Once we were in the basement, we really couldn’t go past the front door of that basement.

Average day I think, the first couple months you know we still had some provisions like food, and we’d stretch it out. We had flour, we had rice we thankfully—they cut off water and electricity pretty quickly so we had no electricity, no running water—we were lucky to have a neighbor that had a fresh water pump and so she allowed everyone to share. It was off of a street, so again, you had to be careful of when you [went], but at least we didn’t have to wait for the water trucks. So we had water.

I remember—my birthday is in May, or, we literally moved in the basement in April—and that’s the only birthday I remember. And my mom made an egg-less cake. It was her first time making it because we didn’t have eggs. It was actually pretty good. I don’t know where she found chocolate, but she covered it in chocolate. But after that, we—you know, you run out of things. You start to run out of things.

So, my mom, she had saved some German marks—she had been exchanging Bosnian, or, you know, Bosnian money into German marks over time like as a sort of “savings thing” and all Bosnian money lost value as soon as the war started. [My mom] would try and find vendors, like people who owned stores—you know how we have a lot of small stores?—she would go in and try to find someone willing to take German marks (because they were at least worth something) for whatever they would give us. So for a while, we were able to [find], like, beans, and whatever was available--oil, beans, some flour, all very limited. Vegetables, we started to grow. We planted vegetables in our backyard, in this like abandoned plot of land.

Eventually, food resources, or like humanitarna, the humanitarian aid, started to drop food. So there were distribution centers we would go to and get some. And really the primary source of food the whole time was beans and flour and oil and whatever you could grow. And I, for years after we moved to the United States, could not eat beans because we literally probably had beans twice a day—which is great as a source of protein I am not ungrateful, because there were people who couldn’t even get that if they were cut off from supplies—but it kept us going. And we would grow tomatoes and onions and some potatoes, you know.

We even experimented with certain grasses to see what was edible in terms of making salads [laughs]… just to spice things up a little.

With the humanitarian drops what were those like? How did you know they were coming? Did they drop in random places or were they scheduled?

To a certain extent. The military would usually learn that there would be—there was communication between the Bosnian military and UN—and they would designate areas, depending upon how safe it was. Those usually also tended to be targets of aggression, so, you could, to a certain extent, schedule it, but you couldn’t always drop the food, because people would amass as well.

And those were…bread lines were being bombed pretty aggressively in Sarajevo, so, you couldn’t always amass—you didn’t always want people to come in droves.

So they would maybe drop food but then they would distribute in local houses— that happened in my neighborhood—instead of having one go-to, designated area, they’d kind of spread it around in a neighborhood, and then each neighbor was kind of responsible for like… providing some provisions to a certain number of families so that you wouldn’t all be standing outside in a line somewhere.

You said you stopped going to school during the war. How were days spent? How did you entertain yourself? Did you parents teach you?

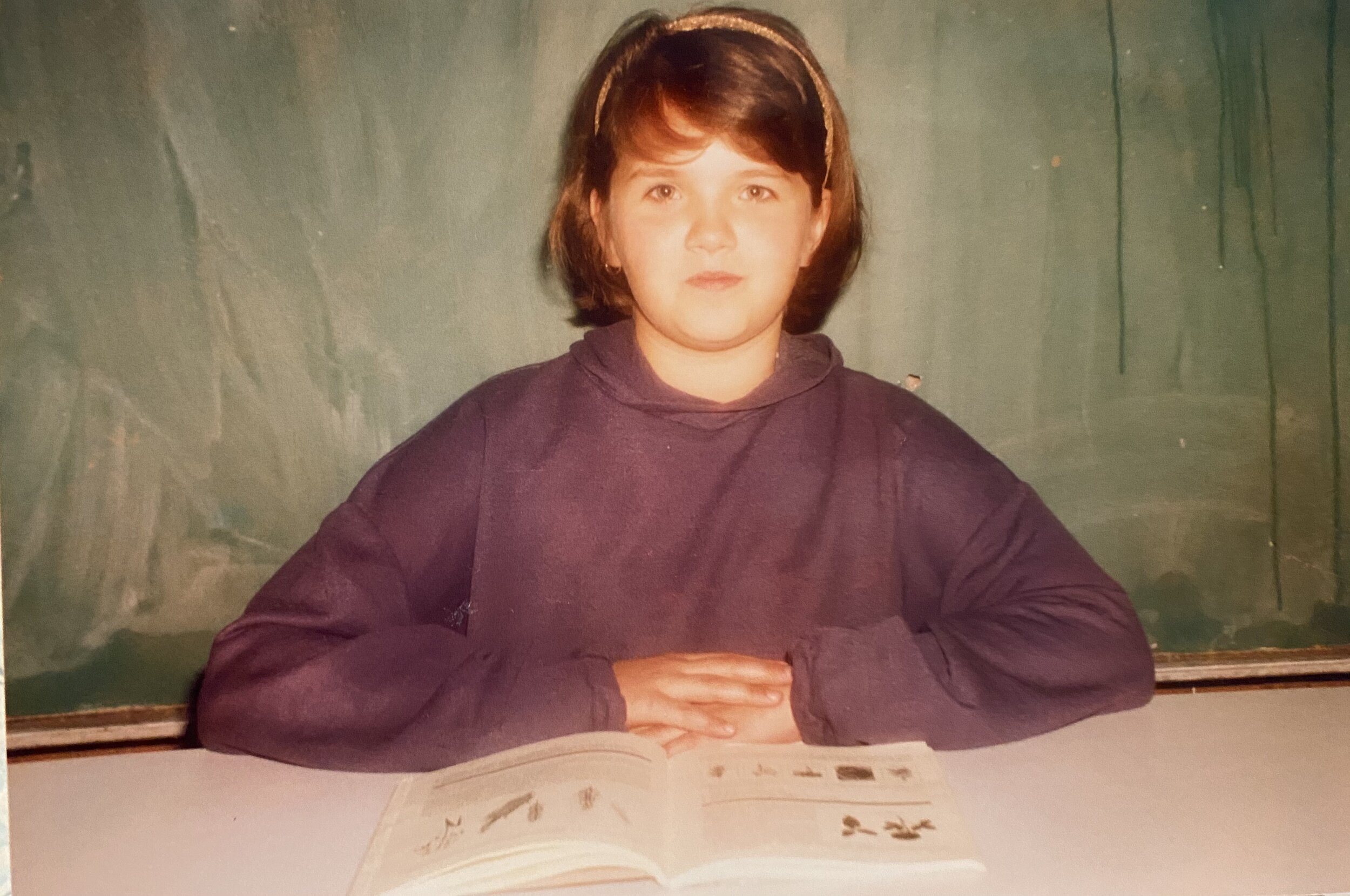

So, initially there was no school. At some point, when we had less heavy shelling days, we had, like, abandoned warehouses or people’s basements where we would have some [school], maybe a couple hours a day. I finished three grades in a year and a half in Bosnia. I had, actually, a wonderful teacher because he was a retired teacher. And he volunteered to teach me and the other kids in my neighborhood. He’s still probably, to this day, my favorite teacher I’ve ever had. He was just the loveliest man. He passed away, he was quite old at the time, so he’s since passed away.

When it first all started, we had books all the time, we had a children’s set of encyclopedias, so my mom would just kind of have us read and entertain ourselves with that. We as kids probably just drove her nuts running around in a basement in a tiny little space. I learned how to play cards, poker, very young—what was it called… Rummy— We kind of made crap up in the basement and did it, just to entertain ourselves, you know. Because we were [young]—I turned 6 and my brother was 8, and you have a lot of energy and you can’t go anywhere. And we would… how do you say it— do kolutove—like we would roll for hours, until [we got] dizzy. [We’d] just keep doing it.

I don’t know as a kid, you’re kind of just trying to get through days in a way that it’s not too boring. Sometimes, we had a couple neighbors and a couple kids, [and] their parents would let them come to our basement because it was just across the yard. And sometimes, we would just play in one of the basements. Um, we would play there. We’d make up games… sometimes war games which is really kind of sad. Because all kids do that, but in the context of war, it was interesting that we were also making war. But it was also sometimes like silly stuff, like playing house and stuff like that. Nothing really…

I will tell you, when you’re in that situation—like I said I really only remember my first birthday— unless it was a-like a direct threat, like there was an attack or it was more violent, You don’t really distinguish the days. They just kind of roll one into the other. I remember, you know, the first time I had kifla after, two years of not having one. Someone got some, and they passed it around the school (like the makeshift school that we had) with some warm milk. That stands out.

These things that were a break from the monotony of it stand out. The attacks in the neighborhood—we were about a quarter-mile from the front line, so when they would organize and attack us—you remember those. I remember a grenade hitting into a house. I could name maybe ten, fifteen things, off the top of my head, in four years, that I actually remember as distinct.

On the monotony of it all—did you fully understand what was happening as a kid? Or is it more retroactive understanding now? How did you make sense of those moments as they were happening?

I think my parents were honest. You know, my dad would be gone (because they were essentially made part of the military, and you know they wanted to, they were defending their own families), he would be gone for a couple of days at a time at the front lines. And so my parents told us what was going on to the extent that I think was necessary: “We are in danger, there are—the aggressors are so close.” I didn’t understand how close until I went back after we moved away. Because as a child, everything seems bigger. And so when I actually walked that distance and I realized, you know, what a quarter of a mile is from the house, it was kind of crazy.

But my parents were very much “you don’t step out into the street.” Which—I made the mistake once and I had a bullet whiz right above my head—and so you know things like that. So as a kid you … I just remember feeling scared when the attacks were happening. My dad was also injured in one of those attacks in ‘93, and so I remember him coming home injured, and I would have dreams that...like, the Serb aggressors, that they’d cross and they were in our house. So I think you’re internalizing all of this, not necessarily [understanding]. As an adult I think your fear is probably bigger in the sense that you can imagine the awfulness of what could happen, but as a child, it’s just an immediate sense of danger and disruption and you see all of this trauma around you.

And you’re seeing people wounded, you’re seeing people get shot, or you’re seeing things that bring it home for you. So even if you don’t understand the larger picture of why things are happening, you understand your day is dangerous.

You mentioned the grenade hitting your house and bullets whizzing by you—how do you make sense of those moments? Are there specific stories like that that feel very real or distinct?

Yeah, so.. A couple stand out. In terms of the grenades, the first grenade that hit our house actually hit right in front of our house. And that one stands out because my dad had just gotten home from the front lines, and my mom had offered to go upstairs onto the first floor (not on the second floor where we used to live but the first floor) where they had a small kitchen, to like slice up some, I don’t know, onions for him. And he goes “no, no, I don’t need it,” and she goes “you sure?” and he says “I don’t need it.” And within two minutes, that grenade hits in front of the house and it just shatters that kitchen. That stands out because that was...you, as a child, are hearing that your mother almost just died. Everyone was saying it, and I was, you know...I don’t think she could have survived something like that if she was up there. So that stands out as that first sense of real, real danger. Something could happen to your mom, which is a devastating thought.

Second time a grenade hit was actually a non-exploding one, like a tank grenade (I don’t even know if that’s the technical term for them). It actually happened to hit between the basement floor and the first floor, like the cement block [in between the two floors]... It didn’t go through it, it actually bounced off. But I was on one side of the basement room when it hit and I landed against the door across the room. It just throws you, the level of that... just that intense force of something like that happening.

So, that I can remember, there were three times that I think I was distinctly in danger [of getting shot]—I never got shot, but [in danger of] being shot. The first one was when I ran out into the middle of the street following a ball my dad got me. I left the basement, my mom didn’t know (I got in a lot of trouble for this).

I had a ball that my dad had gotten me before the war, and it got out into the street and I ran out there, and as I bent down to get it, a bullet like shaved the top of my head.

And so I remember that sensation because 1) it hurt, but 2), like it..you do in that moment, even as a kid, realize that you almost just got shot and that you probably almost just died, and as a kid, I would have not distinguished death from injury at that point.

Second time, I was with my grandparents who were a neighborhood away. And my sister had just been born, which was not good timing (she was born in ‘93, right after one of the worst attacks and my mom actually went into labor during that second attack and it was just awful). But I stayed with my grandparents for a while to help her out, so that she wouldn’t have three little kids, essentially, to all take care of. So I sat on the front steps of the apartment that my grandparents were living in—

And it wasn’t their apartment by the way, they they had to run from their home, and my dad had to go and get them through an underground tunnel that was a tunnel that they built connecting northern Sarajevo to like this southern little, south-of-the- airport-region. That was their only contact after a couple of years with outside world. And my grandparents ended up in Sarajevo in an izbegliči centar, a refugee center. And he went and got them through this tunnel. But anyway—

They were given an apartment. I think it was just an abandoned apartment (the owners no longer lived there), to live in during the war. And so I stayed with them and I was sitting on the front steps for some reason, just probably bored as a kid trying to figure out what to do, and a bullet hit right in front of my toe. It was the weirdest thing. And I ran back inside because I had also been told “don’t go outside.” And I kept breaking the rules.

Because that’s the other thing like about being a kid, as much as you understand you don’t understand that it could happen at every time. You don’t understand when they tell you that you’re always being watched. You think you can just kind of sneak out and no one will see you because that’s how children think.

And the third time, my brother and I were actually both staying with my grandparents at the time. We were very sick and we ended up having to go to the doctor (we had really high fevers), and we had to get some kind of vaccines. And on the way back with my grandma, we were crossing through on some street, and bullets just start whizzing right by us. And—you can feel them, like you can actually feel the air moving around you—and my grandma had a friend that lived on that street who saw us and just ushered us into her house.

So those are three distinct memories I have of that. Very grateful I didn’t get shot—and that no one [in my family] did, not my brother, my grandma.

Was there someone who really helped you during the war?

I think my mom’s parents. They were kind of a little bit of sanity for me because they were just such a lovely couple. So it’s not helping physically in any way, it was just helpful mentally to be around them. My grandfather was just such a kind man. [For example], I wanted to write and I wanted to keep a diary for some reason, when I was about 7 or 8. And he found—you couldn’t find paper, you know, simple things, you can’t just go to the store—he found a notebook somewhere, semi-used, and he ripped out the used pages and he gave it to me with a little stubby pencil.

Or, you know—it’s true that we didn’t celebrate christmas, jelka, christmas trees, are a non-denominational thing in Bosnia, or at least in that region. So, we wanted to decorate one for new years. And we didn’t have anything to decorate with (clearly). And he found cotton somewhere and some old newspaper, so we made snowflakes out of the newspaper and put cotton up as a decoration.

Those, just as a child, those stand out because they’re a sense of normalcy. And we’d play cards. And every once in a while, the electricity would come on and we’d watch TV. Really normal, like you were back in, just in a normal place, like you didn’t have to worry about being in danger. In terms of others, I would say, really it was just probably just getting to leave. We got help really externally from my aunt and my uncle. My aunt, who’s Serbian, and my uncle is my mom’s brother. They actually left earlier than we did to the United States and they helped sponsor us. And they left because they were an interfaith couple, so they were some of the first targets in terms of aggression, because 1) she’s a traitor for marrying a Bosnian, and 2) how dare he touch a Serbian woman. So you know it’s that kind of, you know, they both could have gotten in some trouble if they’d been caught.

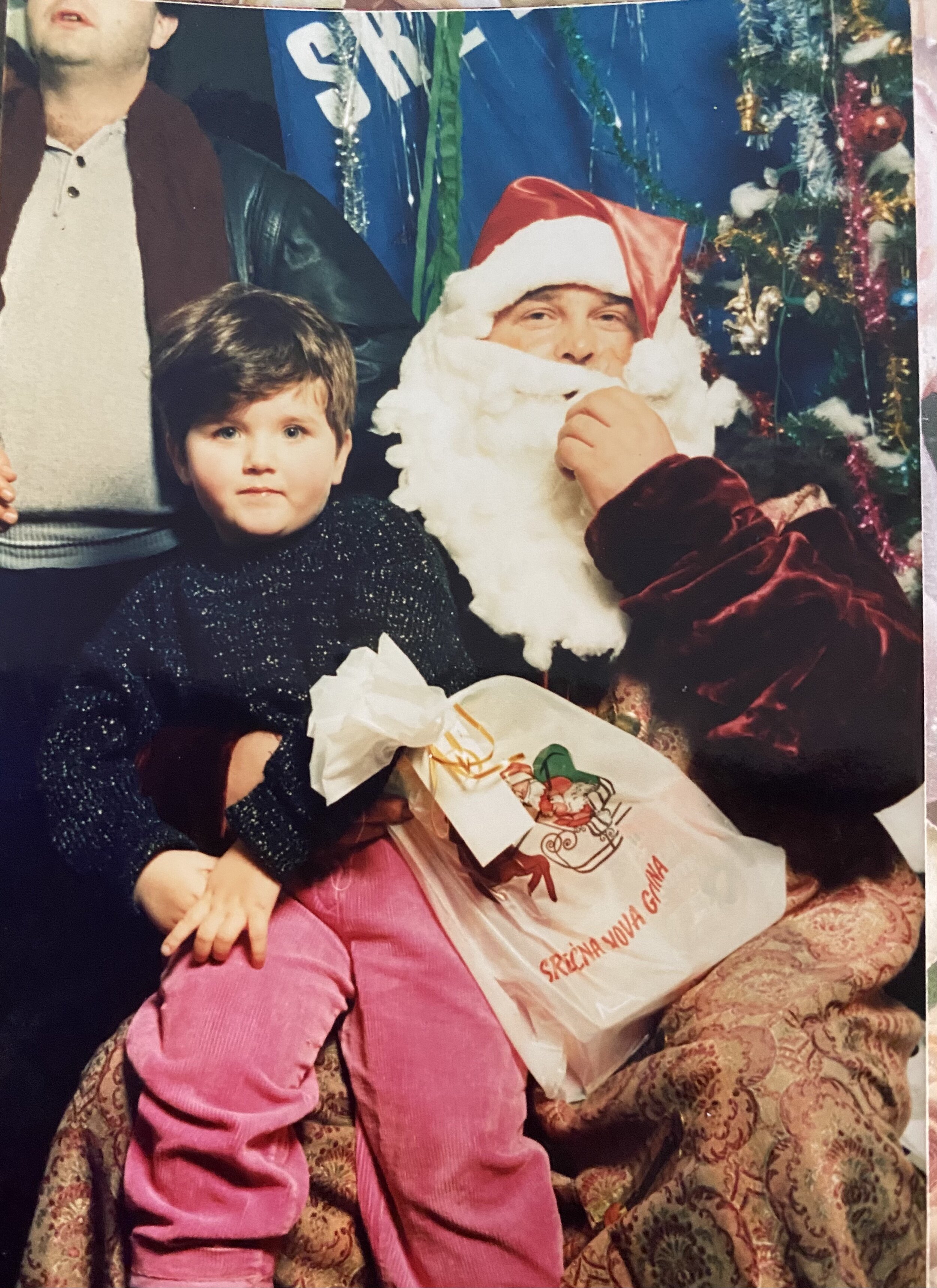

Birthday at grandma and grandpa’s place before the war

So did they leave right at the beginning of the war? Or right before?

So my aunt took my cousin, they only had one child at the time, he was... I think maybe 3. And she actually went and stayed with family in Serbia. But she taught her son not to say his father’s name, because it was a Muslim name, and she was staying with family in an area where like no one knew her husband was Bosnian. He, on the other hand, he left and escaped to Slovenia and hid in the forest because Slovenia wasn’t taking refugees at the time. Somehow, I don’t remember how in their story, they reunited, but they somehow got asylum and emigrated to the United States. So they, with another organization, and this wonderful woman named Joyce who worked with that organization in Colorado Springs helped to sponsor us which is how we got papers in 90...between ‘95 and ‘96, to come here.

You were talking about how you left and sort of that whole process--

Yeah, so because my dad was technically part of the military, so we couldn’t really say we were leaving, because every able-bodied man was essentially just drafted to be in the military. So we couldn’t say we were leaving.

I remember it being a strange day because my dad’s parents and his sister (his older sister) were there. And they obviously knew we were leaving. But we couldn’t really take anything (we didn’t have much), but we had one duffle bag. We couldn’t look suspicious that we were leaving. So we left on foot, actually between houses, until we got to this bus that took us to Croatia. And we stayed at a refugee center over there. It’s the first refugee center that you get dropped off if you’re on this path of coming to the United States and you had 40 days to get your paperwork approved. If your 40 days are up, you then get moved to this like secondary housing, which we never got to thankfully, but it was described as worse. We at least had our own room where we could stay together as a family. This place, apparently it was all shared facilities and like it was…not great. We got lucky and we got the paperwork approved. But it was a process, like you literally had to go and interview and you had to explain that your situation was bad enough and you were in enough danger to leave.

Once we were approved though, we borrowed money from an aunt in Germany, I think, to get tickets. You had to purchase your own plane tickets to leave, which… when you don’t have any money is a little bit difficult. But that’s sort of the whole idea which is if you’re being sponsored, they assume you’re going to come up with the money somehow or someone is going to pay for you. So we borrow the money and it was the first time i’d been--I was on a plane ever—Because the war started right before I turned 6. And before that, we really just drove. We went to Croatia, we like—you took the car you know and you go on vacation.

[Anyway]. It was a really long trip [to the United States]. I think we had five stop-overs, it was just not direct at all, probably because it was so cheap, uhm. But I remember, like trying to sleep on a bench, just being really exhausted on the last leg.

But I, and I remember landing finally in Denver and seeing my aunt and uncle and it was this sense of relief like, like we’re finally “we’re in America.” I remember being so surprised as we were driving—you know, the United States is so big— I was surprised that it wasn’t more lit up. Because it’s like I-25, and there’s like nothing between here [Denver] and the Springs [Colorado Springs], especially then, I just remember being like… “Wow it’s really dark in America!” Because it was night time… there was just no sense that like you had come to a big place.

What did you bring with you in that duffle bag?

Just a couple of changes of clothes for us kids, for my parents, for my sister. My mom did take the baby blanket that all three of us had used. And she took one [stuffed] bunny which my little sister was playing with but it was my bunny when I was a little kid. And she took a few pictures, not very many...I would say under 50 pictures. I think that’s kind of it. It was whatever we were wearing—the shoes we had, we didn’t have any other shoes. I mean, as growing kids we didn’t, it was hard to find clothing—So I mean it was whatever the hell we had we kind of just used what we were wearing. We just had to wash often. With like, heating water on the stove, on the wood-burning stove in the basement.

How was it in the refugee camp? What was it like living there?

Uh, you know, it was… okay, I guess. It was one room. There was a communal kitchen, they would serve you...kind of like you think about school lunches here. They had somebody cooking and you’d go, you’d have to go at a specific time to get food. It wasn’t great food and also things we were really not used to. It was the first time I had those readymade, canned ravioli, which I still don’t like, they still taste gross.

But I remember having that and being like “what is this?” I’d never had them before in my life. So. Can’t be too picky coming out of a war, but I remember kind of thinking the food was kind of gross. But you kind of make it work. And I remember being really worried about the 40 days. And I remember asking my mom, “How many days have we been here?” You know, to help me count kind of a thing. Because I was really worried about going to this other, what seemed like, scary place. That if you go there, you’re almost guaranteed not to get approved, and then what do we do? So I had this fear.

When did the war end for you? Was there a particular moment when you felt, “Okay, it’s done, and we’re okay.”

I think when we left. I mean the Dayton Accords were signed right as we left, marking the end of the war, but really it was still pretty unsafe, and you couldn’t really trust, that...yeah there’s political talk happening, but we didn’t have regular electricity to even watch the news, so you don’t really know the level of safe or unsafe or how close troops were other than what you could immediately see. So. It was really just leaving.

When you left Sarajevo? Or when you leave the camp? Or, what stage of leaving?

Probably when I left the camp because I don’t think I distinguished between being in Croatia and being in Bosnia. For me it was a continuation.

What was the bus ride like from Sarajevo to that camp?

Um, nothing I remember really specifically. Honestly. I remember feeling a sense of relief that we were starting our journey… it seemed… as long as we could be on the bus and go. I remember having some fear about crossing into Croatia because if [our] paperwork— like if you get stopped at any point, if anything is off, they’re sending you back. I remember having some trepidation and my parents talking about that like as we got to the granica [border],but once we passed in Croatia, it was like okay, now we can go to the next step.

What was it like being a refugee in Colorado Springs?

Yeah, yeah, [laughs], I mean it was weird.

I didn’t speak any English, and I’m a talker, I’m an extrovert. I knew how to read (because I was jealous that my brother could read at 6, so I sat next to him and my mom and taught myself to read and write alongside them). So, what I would do is, I would try and find books and translate them. I would watch old movies to try and learn English.

We enrolled in school pretty much almost immediately and I remember feeling so disassociated from everyone—schools are nothing here nothing like they are in Bosnia and kids are much more interactive and I was like “are they allowed to talk?!” And, you know, you’re an outsider. And if you don’t understand the language you don’t understand the culture. So you could see that the kids wanted to say “hi” and they’d see that you don’t understand, so they’d just speak louder and slower thinking that’s what’s gonna get it.

So initially it was weird, I always looked forward to the end of the day to see my grandma (my, my mom’s parents actually came over with us), and—to your point!—she would make burek, pita, near-daily, at least from what I remember. And I remember this feeling of coming home because I was coming back to the language I understood, the food I understood. I remember, the first time I tried a hamburger, I thought it was the most disgusting thing I’d ever tried— like a McDonalds hamburger— and I was like, “Why does everyone want this?!” Because you know, the happy meal is hyped up...I didn’t get it. (I absolutely love a good burger now).

But then you know, over summer break, we enrolled in this daycare that my mom actually worked in (because she didn’t have any other skills and there were these other Bosnian ladies that got her the job). So we got to go to daycare for free, and through that summer program, and then ESL the next year, I learned English. And I then went to... so fifth grade was when I went to ESL, I graduated from the program that same year. Then sixth grade was fine, I was making good grades, I made friends. Seventh grade, I was student of the year, in my class, because I was such a little overachiever.

So like I, I really—as soon as I felt I could— I had this intense desire to learn English, to learn the American culture, and to fit in. I even had an accent when I first started speaking English which I was just like “Nope, I’m gonna get rid of that.” Which, you know, there’s this sense that you don’t want to stand out at that age anyway, it’s like right at 10, 11, those are really awkward ages. So I would practice. And I really worked at embracing every opportunity, and, uh, I think it worked out relatively well.

Do you go back to Bosnia now?

Yeah once I started going back after college I would go every year, every other year and I would go for like a month at a time. I would just save up annually and go. With COVID, that’s interrupted things, but I’m hoping next year, next year I could go. I love it. I love it now. and I have a sense of peace around it.

But it took time and going back to get to that point.

I think I had to want to go back. Because again, I think I really invested in becoming Americanized, an American. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to be Bosnian, but it felt like the most important part of my life was here. And so I was prioritizing it. As I got older and I started going back, again I think what hit me was that sense of coming home. And I think that’s when my perspective started to shift. Your first ten years are very formative years. And you don’t...you’re not not that person anymore. You just...you take those experiences and you become the person you are today based on all of the experiences combined. So, yes, I appreciate it now, I do love going back, I don’t know if I would ever long-term live there again, but you know, I don’t rule anything out. So.

How do you identify now? More as American, more as Bosnian, with both?

I would say both. I would say both. And sometimes I have to remember I’m not from here [America], because it does feel like I’ve lived two different lives. Interestingly. It just does. You kind of feel like there was a start and a stopping point to the first life and then a start and today here. So sometimes I have to be like, “oh that’s right, I lived through that, I’m from Bosnia.” Which I think is a good thing.

It’s part of that… it’s that resilience of “you did live through that but it doesn’t mean you can’t have this amazing life.” In fact I think it means I probably embrace it more. And really fight for it.

And I have an intense sense of pride, for my ancestors, for my family, living and passed. Like a real intense sense of gratitude and fascination because as I’ve also gotten older, I’ve gotten curious about my family members, both living and that have passed and their lives. And they’ve lived such—because Yugoslavia is just such a short blip in the history of that area—they’ve lived such interesting lives there’s such a rich history there. And all that strength, all of that combined desire to survive it all, all the instability in that region. I think it’s created the people who they are, which makes me love them more.

Yes they’re a little more tough—people tell me that today, I think I appear, even though I’m a mostly happy person, people tell me “No but like things don’t phase you”— And I think that’s probably true. But like my mom, my mom’s not an alarmist, neither are my grandmas, and I wonder if that’s just sort of that history of, like “Oh well, another day, another thing to worry about.” That “we’ll figure it out.” There’s always a sense that something is always going to be wrong. So just deal with it.

You talked about when you went back and you sort of saw that distance and that made it more real. Do you go back a lot, how do you feel about Bosnia/Yugoslavia/all of that now?

Yeah, I’ve gone back a handful of times. The first ten years we were here we didn’t. It was really expensive and I was a teenager and I don’t know that I had any particular interest in going back immediately. I think it was a sense of, not that I didn’t want to go back there or that it was disconnected, but it felt like we were...the focus was on establishing a life here, getting my education getting a job, and eventually I would go back there. That was the kind of thing I was thinking about.

The first time I went back was after… college? Yeah, the summer after college before I went to law school. It was strange because I’d been gone from ‘96 to 2008 and yet we landed and I felt like I’d come home. And I have that sensation, uniquely, every time I go back. And I don’t feel like I’m not at home here [in Colorado]. I was 10 when we moved here, or turned 10 literally a month later, so this feels very much like the place I grew up. And yet, every time I’m there—even the smell feels somehow familiar. Hearing the language constantly around me, immediately transports me back to feeling “Okay these are my people this is my country.”

Going through Sarajevo was a bit more… it was heartbreaking to be honest. Because you could still see the remnants of the war, not every building is fixed. Sometimes when I’ve gone, it’s been less clean than others (It’s been better the last couple of times, they’ve done a better job of making sure that their trash collection happens and all of that stuff).

Walking to—like that quarter of a mile to the front lines, now where the tunnel of hope is, because that’s where the start of that tunnel was was weird. This last time I actually made it a point to go to those places and actually look, like look at the pictures [and everything]. Because it it was a little too difficult initially to go back into those spaces and try and relive them... it was fine when I’m not there, to talk about these things and recount the experiences, but being in the space and like feeling those feelings of what it was as a kid to be in that area was...was too difficult.

But this last time i went, which was actually Summer 2019, right before COVID hit, my brother and sister and I went together for a month and we actually did a bunch of...Like we went to where the Olympics were held, and we took the gondola up that overlooks Sarajevo, which we hadn’t don’t since we were kids. We did a bunch of things you’d think the tourists would do but kind of like we were relearning the city. But, we also did the...some of the more difficult pieces of seeing the memorials and the preservation of the things that have occurred during that war.

What kinds of changes in Balkan culture, either there or in the US, have you seen, either before the war, during the war, after the war?

I mean before the war, like I said (and this could be some idealization too as a child), but I had no sense of “we’re different from anyone else,” or that anyone else was different from us. Everyone was—I believed—that everyone was the same and wanted the same things. Like very much that childlike mentality. My parents were—you know, they had their jobs, they worked, they’d come home, we’d talk about, you know, what our next vacation was, how was daycare, what was I learning, what was I doing.

During the war, I think there was just a sense of shock, but people were just trying to figure out how to survive it. We have a thing in our culture where we just laugh at the most inappropriate things, like that was escalated to like the nth degree. Like Nadrealiste came out like right before the war and even did a few episodes during the war. they were a very famous like comedy troupe, so like they even they recorded an episode and were making fun of things in the war. Like for example, because the the Serbs, the Bosnians, and the Croatians were now distinguishing themselves, they [Nadrealiste] would pretend like they couldn’t understand each other and they would need an interpreter. And so that was the joke. But it was also dark because this was...this was so unique and so unlike what Bosnia was. So, things like that stand out.

The people I think were just trying to figure out how to make it through is as is, I think, the human condition...to survive it. And small things, like women would pride themselves on how to make that cake with like three ingredients, you know. You can’t make baklava but could you, like, pretend-make one? What is the texture of a nut? Like what could you do to make it taste like that? And some women did a really good job. And you know, they would occupy themselves by trying to help, like making food for soldiers on the frontline. And there was a sense of this has got to be over at some point.

After the war, now that it is over, and I’ve seen wider groups of people and I’ve been in contact with more people (you know obviously in the war you have your tiny group of people that you see and you don’t go anywhere). You see how much more devastating [it was]. Like I had family who were in the concentration camps and they were killed there and they were found after the war. So you’re learning where all your family is, because you didn’t know, you have no—I mean, you can’t call ‘em.

So, after the fact you just saw the people—like that natural instinct of survival for a lot of people—kind of die out when they realized the level of devastation that had occurred when they weren’t even aware. Like who all died, how they died, the level of destruction, going back to their homes that they’d been forced to leave and seeing it all just torn apart.

So I actually think, especially those who lived, through it and the older people and those who lost immediate family members, it’s been very hard to get over that. And I can’t blame them for that. Even though when I go back there I just want to say “We just have to move on.” I know I have no right to say that, because I’ve been given that opportunity to do that and they’ve had to stay.

Were you able, when you were in Sarajevo, to go back to the house and see all of that? What was that like?

I mean, we never had to leave the house, which was, really, really good. We were lucky that we had a great basement—Which my grandfather built because he experienced WWII and he put a wood-burning stove in it, actually. And my mom made fun of it before the war like, “Babo, why would you need that when there are electric stove?” And he goes, “You never know Snaho, you never know. “ Like that was his thing.

That’s a sad irony.

Yeah exactly! She goes “I spoke so well of that man every day.” And it’s true, we did— I mean you heat yourself, you cook on that [wood-burning stove]. We were one of the only houses that had that,

We were one of the only houses that had an operational basement like that. You put sandbags around the windows (it was relatively underground but you had about a foot of window) and you were basically barricading yourself.

Going back, it was tiny from what I remember it being. You know, especially [compared to the] space available in the United States. It was tiny. I go, “Mom how did you even try to raise us in that tiny space?” Even before the war! Much less during the war, it’s just… perspective.

Going back to my grandparent’s apartment—they had to abandon that, my mom’s side— they had done a lot of renovation by the time I came, but it was strange to see it because so many of my pre-war memories were there. My dad’s parents though, they had a farm in Rogatica, and that was burned down. And that was never rebuilt. My grandfather, he lost the ability to use his legs during the war—unrelated, like not a war injury. He had a back pain and then some nurse gave him some shot and he wasn’t able to walk after that—So he was always so sad. And he always wanted to rebuild because he’d already rebuilt that area twice because he lived through WWII and, so for him...I think he died devastated that he couldn’t bring back to like the former life that it was. And it was beautiful, you know, we’d go sledding there, this giant hill with this beautiful open nature.

Is there something that you want Americans or non-Balkan people to know about the war? Or about Yugoslavia, or any part of it?

It’s both as complicated and as simple I think as people want it to be.

Which makes no sense, I know. It’s complicated in the sense that you’re talking about… these are non-monolithic groups, non-monolithic, spaces, countries. As much as people wanted to say, “it was a fight between the Serbs and the Bosniaks,” it’s not true. You know. It’s much more complicated in the sense that you had just as many Serbs and Croats suffering in that war, living in occupied and surrounding territories, as you had Muslims that were being targeted. It was this idea of, how do you...you’re not just a Serb or you’re not just a religion, you are a person who had this history behind you or before the war started. You don’t change the person, you don’t just start hating for no reason.

On the other hand, it also was as simple as: there was a genocide of the Muslim population.

And what’s been most difficult, I think for those who survived thiswar, is this initial labelling—and there was a specific, it was political from the West in terms of calling it a genocide, they didn’t want to have to intervene under the Geneava Convention I understand this. But to label it as an “ethnic conflict” just... In fact, “ethnic cleansing” was a made up term to not use “genocide.” Ethnic cleansing is just a misnomer for genocide—But they wanted to call it a civil war—only Bosnians against Bosnians. And that’s just certainly not true.

So it’s as simple as: there was this tragic event. But there were complexities underneath it because we’re talking about people being complex and not having one identity without any context or history.

So, I also really hope… I don’t want to get into politics of the United States today and I certainly have my perspective on what happened over the last four years, but I will say, when people talk about, as “is as everyone being too alarmist?”—

you only get the system and the peace within that system that you help and actively want to be in place.

As long as you believe in the system, it stays. When you stop believing in that system, or you think it should—we should just “shake things up,” that’s when you have things like that war. So when everyone’s talking about “Oh everyone’s being too alarmist” No, I think that’s when you pay attention because those changes weren’t overnight in Bosnia.

As I said, talk happened for years, people talked about Milosevic and Karadzic actually. I mean Karadzic made a famous speech on the congressional floor right before Bosnians voted to emancipate themselves from Yugoslavia, along the lines of like, “You seek independence we’re going to attack you.” And no one believed him and he did it in our version of congress, like the congressional floor. So this idea that it can’t happen here? It’s nice to think that, but everyone thinks that.

So you need to fight for what you want to preserve.

And you should never take things like peace and the importance of compromise and the importance of working together against those who would otherwise destroy a system, even if it’s a small group. Because it was a small group, even there. Never take that for granted.

What about something that you want Balkan people to know? Other people who grew up there and are still there?

Continue to want it to change.

And don’t be so disheartened that you completely disengage from the importance of that space and the future of those countries.

Because yes, they all want to leave, but at the end of the day, most won’t. And it’s what you do to try and change it. And it’s hard, it’s really hard. I get that. But, the effort is worth it to get some of that spirit back. We are known for that strength of spirit and again, that really inappropriate sense of humor, but it gets us through a lot.

I guess I want them to know that there is better on the other side of it, but no one is going to hand it to them.

And that’s just realistic. And again, I was lucky to get out, and I will always be grateful, and I know I’m saying this from the outsider’s perspective—but, there is no guarantee they will [get out]. And so if you’re disengaged from the system, from the politics in your country, and you allow the Dodiks of the world and the Vucics of the world, and you allow them to, they’re going to continue because it’s in their own interest. And we don’t want to become Russia. You know. And I think we’re headed down that path where there’s just intense apathy, sort of that Putin-esque where it’s just ongoing, there is no change and no one expects it to change.

And that apathy is easily capitalized upon.

Exactly.