Eldis S., 48

Krasan Polje

“I was a soldier in the the army. I was wounded once. Then, when the war finished in 1995, I was among the first to be demobilized because I didn’t want to wear that uniform anymore. I didn’t feel good about it, thinking about how I was imprisoned and I always had that sense of fear within myself, even as a soldier.”

Okay, I started recording.

My name is Eldis S. I was born March 6, 1974 in Krasan Polje in Bratunac. I grew up there, until the beginning of the war. I finished middle school and high school in Bratunac–for welding– and immediately after school I started working in Titovo Užice in Serbia right before the beginning of the war. My second, third time coming back from Užica, the war started when I was 18, in May I think. 1992. I finished school at the end of 1991.

What was life like in the village? Like in every village, we worked in agriculture, kids played with footballs or on bikes. That was a really free time. We helped our parents with in the fields, cultivating wheat, grain, raising livestock. Really all of us were equal, no one was rich and no one was poor, all of us were more or less the same. What happened afterwards, you know…

We lived in a village where everything was mixed, where it was half Serb, half Muslim, at least before the war. We knew who was what, but it didn’t matter, you know, we all hung out together.

The beginning of the war was like in all of the former Yugoslavia, uh…the Yugoslav National Army occupied primarily Bosniak, Muslim villages, disarmed them if some had weapons, and then stationed those paramilitary units from the JNA– reserve forces, extremists– who came, burned people, killed people, like-like…every village. Like what happened in Croatia, what happened in Bosnia, just like that. You know, we all went through that same system–through the occupation and attacks from the Yugoslav National Army and of course, afterwards, the Bosnian-Serb army.

Our village was attacked in May 1992. Maybe 10 days before that, I came back from Užica on vacation. It was very much a war.

On May 7, I think, they rounded up all of us, men and women, from the village and took us to the city playground in Bratunac, where they separated the men from the women. When it came to me, I was 18 at the time, I was taken with the men, and we were captured and held in the gymnasium of the Vuk Karadžić Middle School in Bratunac. In the same school that I went to from fifth to eighth grade.

There were about 500 men imprisoned. There was a lot of…mistreatment, a lot of killings, a lot of ugly things, like in all of other other concentration camps that Serbs organized for our people.

There were a lot of killings… my brother was killed there, my uncle was killed there, a lot of cousins, friends, acquaintances. Of course, we all knew each other.

There was horrible torture, there was– it’s simply unbelievable to think of what people are wiling to do to each other just because we didn’t believe the same things. Simply for that.

In general, the people who committed crimes were people from outside of Bosnia who came to Bosnia, but there were those “insiders.” People from Bosnia mixed in with them. After being imprisoned there, we were exchanged down near Sarajevo. They dropped us off in Visoko in exchange for some other Serbs, some 15 Serbian special forces that were imprisoned in Sarajevo. That was the beginning of the war. I spent the rest of the war in Visoko, in the house of this one Catholic family who helped me. And in 1993, I enlisted in the army. I was in Zenica for two months in uniform and then after that I was a soldier.

I was a soldier in the the army. I was wounded once.

Then, when the war finished in 1995, I was among the first to be demobilized because I didn’t want to wear that uniform anymore. I didn’t feel good about it, thinking about how I was imprisoned and I always had that sense of fear within myself, even as a soldier.

After being de-d-demobilized, I worked as a bartender at some bar. I also played football, which was paid. Life in the war was hard, uh… there wasn’t electricity, as in the majority of those Bosniak parts, you know. Everyone ran out of food, electricity, people survived however they could survive, they still lived– they got married, children were born in those difficult conditions, there was…there was some life, something normal, when there was no shooting, when-when it wasn’t dangerous, when people weren’t being bombarded with grenades, there were some days when it was peaceful, and people still tried to live some kind of normal life, even though it was difficult [sighs].

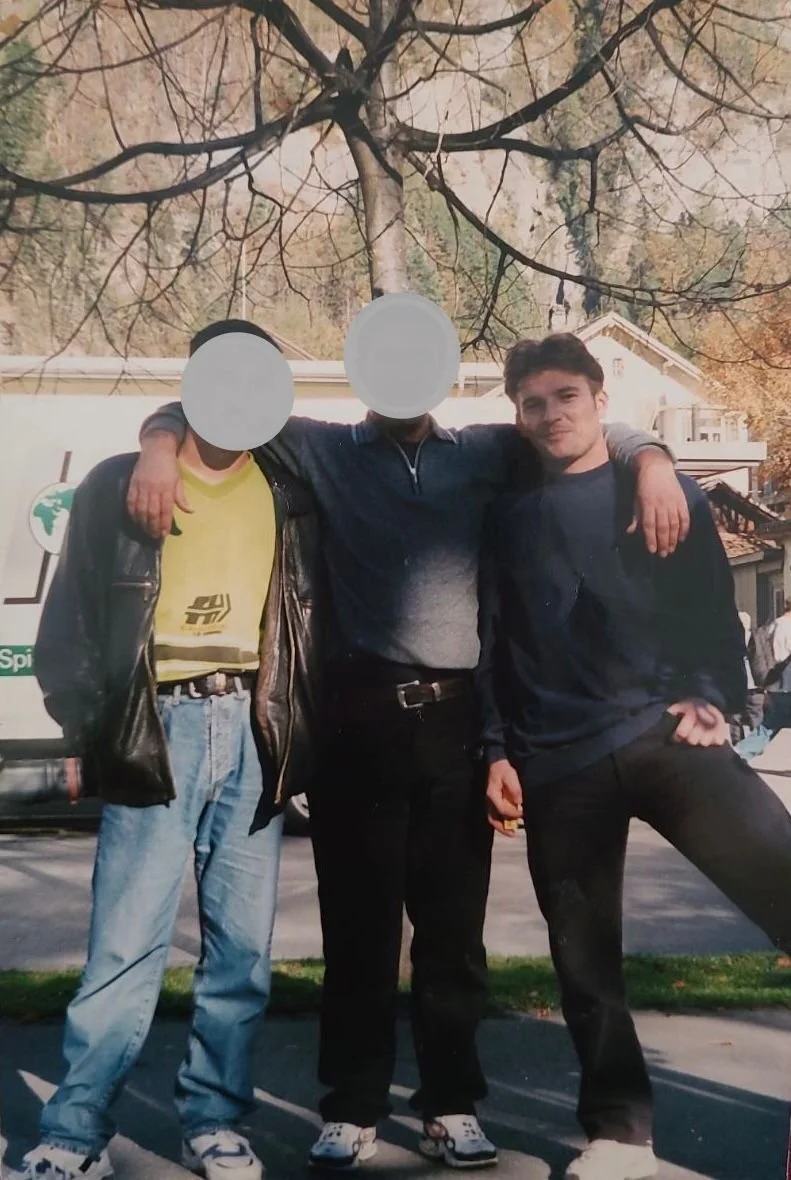

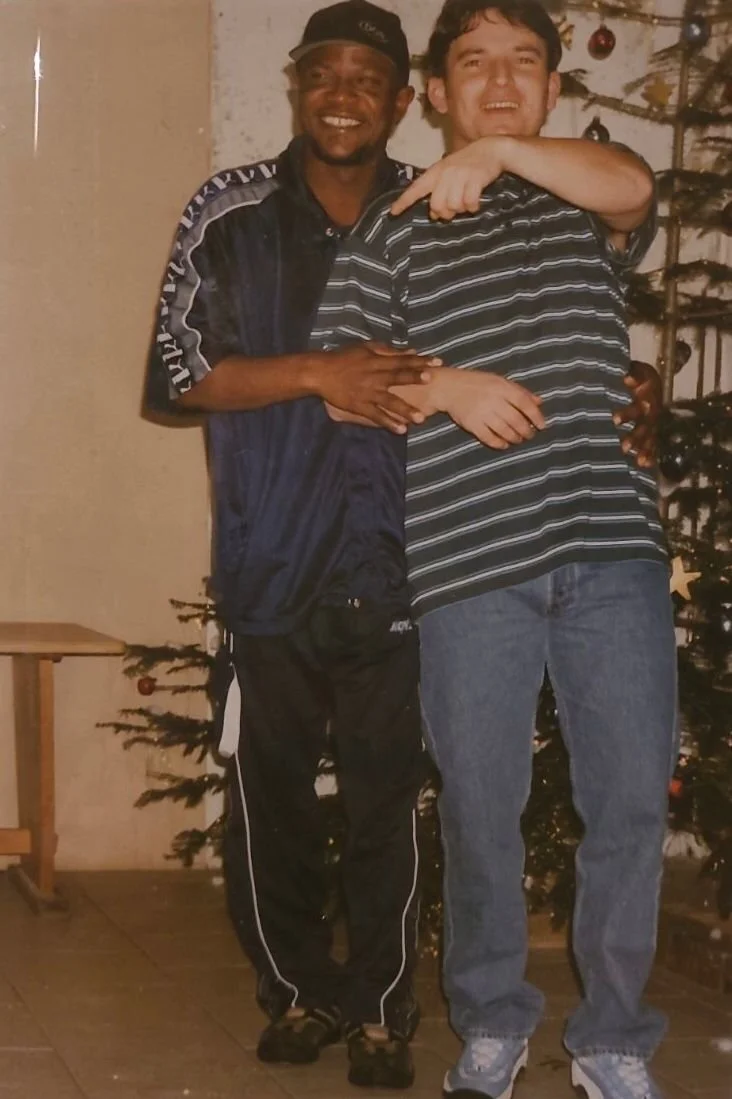

It was around 1999 when I decided to leave the country simply because I didn’t see what I would be able to to do– any profession I could have, how I would manage to live some kind of normal life because I even felt like a foreigner there, in Bosnia. So, 1999– I decided to go to Switzerland. I got married there. Two kids. And so now, in 2022, I’m in Bosnia only on vacation [laughs]. We can talk a bit about that.

You know, now, life in Switzerland is good. Safe. But it’s also hard. The jobs I work are generally difficult jobs, but, you know… I can put up with it and we generally enjoy ourselves when we come here on vacation,when we’re together with family, seeing everyone, talking with everyone, helping each other out as much as we can.

That’s generally, in ten minutes, that’s… you know, the main parts of the story.

Is there a specific moment when you felt personally that the war started?

Pa, when I returned from Užica. As soon as I passed over the Drina bridge, I saw tank treads, the village was more empty than usual, there weren’t people, you could feel the horror in the air.

Then I saw that war had, in fact, come to us… and we all thought that it wouldn’t. That it was still far away from us. Even when we saw on the television that the war was happening in Bijeljena, then moved to Zvornik, we thought, “No, it’ll go around us”– we didn’t have a problem with anybody. That time I crossed the bridge, when I saw that soldiers had control from one side of the bridge to the other, that was the sign for me that the war had come. When I came to the village, I heard that a lot of people had been killed… then I was sure that the war started. That it had definitely come for us.

You mentioned that there was that one family in Visoko who really helped you during the war. In what ways did they help you?

They helped me because I was living in their apartment there for two or three months. I was crushed, severely beaten, and they treated me. They brought a doctor who treated my back and they helped me a lot.

You know, that doctor was a Serbian woman. The family that really helped me was mixed– the husband was Catholic and the wife was Serbian. They had two sons and they decided to help some of the 500 people that were in that camp and they happened to take me.

I bathed there, I ate, because we were really crushed. And after that, they gave me a house in the village I lived in, five or six kilometers from the city, where I agreed to live until the war ended. I stayed there until 1999, in that house. They helped me mainly in that way, they helped me mainly in that way at the beginning, with accommodations and getting treatment and everything. You know, everything. And then after that I lived in that family’s house for seven years in that village.

Ovako, while you were imprisoned in that–

In that school–

–In that school. I know that it’s a bit difficult to talk about this, and you don’t need to go into every detail if you don’t want to, but what was a typical day like? What happened there?

Pa, we were imprisoned, you know…there was one guard that was in charge of us, making sure that we didn’t get past the door. The walls were really high. There were windows with wires and nets so that a ball doesn’t hit the window during PE class.

So we simply sat on the floor, kept our heads down, and they came in, drunk, and beat us, berated us, killed whoever they wanted, we just covered our heads. Always terror.

We didn’t have anything to eat, water came very rarely, you know, we left–we were sent water from outside in crates, in beer bottles, or in bottles for juice, but that was so little for 500 people. People died simply because of a lack of air, because there were so many of us.

There was horrible torture, a lot of people…one night, nine people died from lack of air, of oxygen, because there were so many of us. We would simply see in the morning if people were lying dead, walked on, trampled, because that was one of the fears– that was something horrible, because it’s something that in the normal world you would never imagine. One of those that…if you watched a movie and you couldn’t believe that that kind of suffering existed. We saw it in the films, how people were tortured in Iraq, how they were tortured in Vietnam, how that was– it was like that. Every method of torture possible. And all concentration camps from the Serbian side had the same thing, you know. I talked to a lot of people who were imprisoned, and the majority of the methods were the same.

The same group in a lot of camps were killing and torturing people. The day didn’t different from the night nor did the night differ from the day. So, they could drink at any moment, berate people, kill them, to perform, to call out a list, um… horrible things.

In that period right before the war started, did you see any changes, division, between people?

That started a few months before the war. People started to organize themselves into guards, losing trust between Muslims and Serbs. Everyone went to their side, everyone was afraid. Serbs fled to Serbia, we didn’t have anywhere… that all was all felt a few months before, right at the beginning of the war in Croatia– that’s when you could start to feel the terror, instability, people didn’t sleep in their houses, they were elsewhere, hiding.

That all started a few months before the beginning of the war. Those feelings, that division, to know who was who…everyone kept to themselves. I think three or four months before, it was getting closer…everything was becoming more dangerous and more dangerous, people were leaving, you didn’t see people anywhere, no one went out, no one was tending their land, you don’t know where people are, you know, everyone was trying, wherever they could, to take cover, to not go anywhere, and a lot of people survived like that.

Unfortunately a lot of people believed that if they didn’t do anything wrong to anyone, then nothing bad would happen, that you have nothing to be scared of. However, in the war…that wasn’t true. They died in the war, that honestly lifestyle was zero, non-existent. Life was not worth living. Anyone could kill whoever they wanted, you simply just took and you killed and nothing else. Especially Serbs in our regions–Serbs could do that with us. Because they had power. Their post was the Yugoslav National Army, it was put on their side, it gave them weapons and we were without weapons, we couldn’t protect ourselves, you know. There were places a little farther up that tried to protect themselves, but we were in that position that…we had Serbs on one side and Serbs on another side and, you know, it was the same for us.

And when did the war end for you? Do you have a moment when you felt for sure that the war had ended? Or do you think that there still exists that division between people in Bosnia?

The war finished with the Dayton Agreement. So the shooting stopped, but I don’t think the political war ever stopped.

That’s still happening. That wish to divide Bosnia and Herzegovina, and that we’ll probably disappear, or I don’t know what… but in general I think that the politics now are worse than before. That division– I think that politicians are making that division… that’s the biggest problem. Ordinary people would do it differently, because ordinary people cooperate, work together, connect with each other. Because they need to for the economy, because they couldn’t function otherwise.

However, at the political levels, it’s very complicated because the same parties who started the war– they’re still in power. And they’re still going that way–that division on a nationalist basis, people are being moved ethnically divided. So it’s very, very difficult for Bosnia.

Is there something that you want to say to people outside of Bosnia to know about the war? About what happened?

Something there’s very important that they should know: there was a war of aggression against Bosnia-Herzegovina. Clear aggression. That wasn’t a civil war. If Bosnians hadn’t defended themselves, then they would no longer exist.

And the victims shouldn’t be equalized–not to say that there weren’t dead and victims on all sides, but the number of victims from the Bosnian side cannot be equalized to the Croatian and Serbian sides. That's the most important. Because when you look at all of the mass graves, when they reveal mass, they’re usually graves of Bosniaks. The system was the same everywhere– split up the men from the women and the children and kill the majority of the men. Mass graves that they even had to dig themselves, you know.

The truth needs to be known because now, when you watch TV, Serbian television shows everything bad that happened to us, and they change it to say that it happened to them. They won’t admit that they did that, but whenever they unearth mass graves, the majority of the victims are Bosniaks, from those counties and from those villages. It’s most important that the truth is known, that we died, you know… that we were the ones killed. That wasn’t a civil war. They fought us and they were stronger and that’s that. That was pre-planned. And we didn’t have another choice other than to defend ourselves, however we could defend ourselves. That’s the most important. To know the truth. How it really was. To not believe the media because every media outlet does what they’re paid to do, there’s no free media that says “It was this way, we need to admit it, to apologize, and to do what needs to be done so that it doesn’t happen again.” No, the majority of them– our war criminals are their heros. How is it possible that someone could be a hero if they ordered the killed of 8,000 people in two or three days? So, um… the most important thing is the truth. For everything to be how it actually was.

Do you have something that you want to say to the people here, in the Balkans? And in Bosnia? After the war and after everything that happened?

That Balkans are a place where people are stubborn. People can agree on something in 24 hours and everything will be okay and everyone will live well. But they can also spend 50 years making sure that nothing will be okay and that everyone feels bad, unsafe, the same as in Bosnia-Herzegovina after that war.

So, we’re going forward with more instability, the threats are increasing of some new war, some new entanglement, that someone else here will have some great powers that will solve some of their own problems, like Russia is now doing in Serbian parts, pushing them toward, some– I’d say some new war. And people are uncertain, people are fleeing, young people are leaving, the longer this goes on, the fewer people want to live there and they’ll feel more and more uncertain. So that in some foreseeable future it’s probable that there’s be some kind of war. Until the older generation dies, some people won’t be working, or less, that they don’t have enough, so that, [laughs]...I think that some new war isn’t necessary, because there’ll be fewer and fewer people. So, what should you tell them? Pa, you don’t have anything to say when they’ll do what they want to do. Whatever works for them. Because they’re still going on that national key, they’re still talking about nationalism and everything that surely those parties of theirs will rule again, nationalist parties,

So… it’s best to not say anything to them because nothing will change it.

Maybe great powers, like America, could they maybe have changed things while the war was here?

They could have, they could have– Americans stopped the war. You know, if they could stop this kind of war, I think that Bosnia-Herzegovina could maybe be a functional country, if that was of any interest to them, and if they wanted to.

Mhm. And one last question. The project is called The BUREK Initiative, you know, because we all love Burek. Do you have some kind of story about Burek to share?

Pa, some story, I don’t have that. But I would compare burek with Bosnia and Herzegovina. You know, all of us could be, could come, go, pass, Bosnia survives, and burek is the same. Those two go together.

Bosnia couldn’t go without burek, and burek couldn’t be without Bosnia.